The only problem is it’s not available.

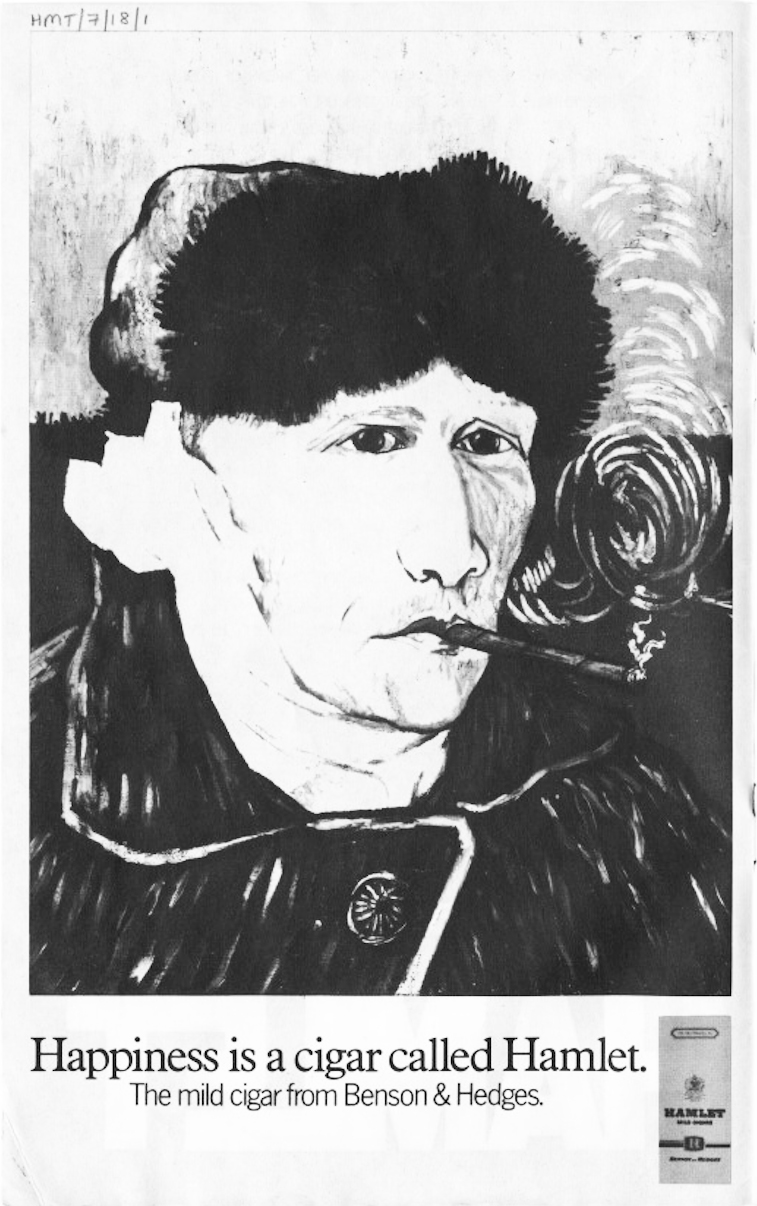

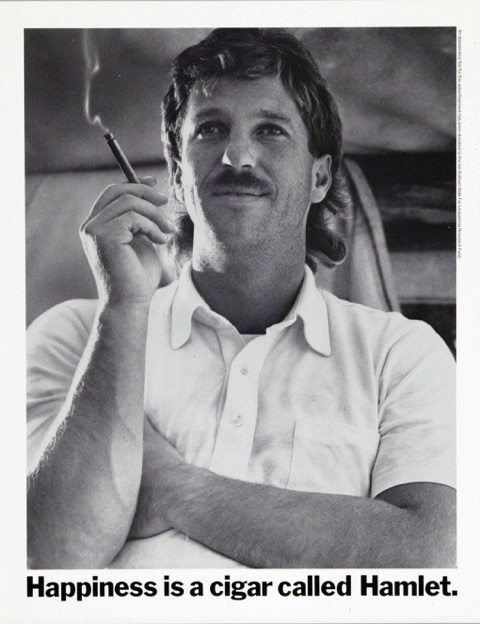

It’s been written by a friend of mine, Mike Everett, as well as writing the book Mike wrote many great ads whilst at Collett’s and Lowe’s, including the Olympus David Bailey campaign, the freaky ‘Wrangler. That’s what’s going on’, Birds Eye’s ‘Dishonest woman’ and a bunch of Hamlet ads to name but a few.

He’s kindly allowed me to feature a few chapters here while he seeks a publisher,

Hope you enjoy.

CHAPTER 1.

The Hamlet campaign ran for a quarter of a century.

Yet the way in which it was conceived could hardly have been more humble.

About the hardest job any advertising writer and art director can be given is that of creating a new television campaign.

Once you’ve got your head around the product, the target market, the product’s competition, and the competition’s advertising, you and your partner are left alone, staring at a blank sheet of paper. In theory, what you now have to do is simple: work out a structure that nobody has ever used before, say something that nobody has ever said before, in a way that nobody has ever said it before.

And don’t expect the creative brief to be much help, either.

Usually, this piece of paper raises more questions than it does provide answers.

Imagine, then, being Tim Warriner and Roy Carruthers.

They are sitting in their shared office on the fourth floor of CDP’s Howland Street building staring at a brief that asks for a TV campaign for a new small cigar that is being launched by Benson & Hedges.

It is 1964 and the name of this cigar is Hamlet.

Tim and Roy are in good company. Arthur Parsons, John Reynolds and Alan Brooking sit along the corridor; Mike Savino is opposite. In fact, they are surrounded by a galaxy of creative stars presided over by the brightest star of all, Colin Millward, the creative director.

You might think that being amongst all this talent would help the creative process, but not necessarily.

The intense competition of your peers can inspire, but it can also stifle.

Tim and Roy have to overcome their fear of failure and bring their confidence to the fore.

They must determine to produce one of the finest campaigns of their lives.

But, as is often the case, when you try that hard, nothing comes. Well, nothing good, anyway.

You can work your balls off and still end up doing average work.

This is why creative people develop techniques to provide themselves with inspiration.

Some do these things instinctively; others have to learn.

Generally, it has to do with what John Salmon, creative director of CDP in the seventies, once memorably described as ‘displacement activities’.

As its name suggests, this is doing something that displaces what you are supposed to be doing. For example, writing a TV campaign for Hamlet Cigars.

It could be going to the pictures, going to an art gallery, or going to lunch.

Or it could be when your working day is over, when you start to relax, and so does your brain.

The most famous example of a displacement activity is, of course, the literal one of Archimedes.

He cottoned on to his famous principle that a body displaces its own mass in water when his own body was doing just that, as he lay in his bath.

Tim and Roy had been working for a few days on Hamlet, but didn’t have anything yet that they considered good enough.

It was the end of another miserable day during which they had made little progress.

To add to their gloom it was dark, cold and pouring with rain as they traipsed down the steps of 18 Howland Street and headed for the bus home.

The bus arrived and they climbed the stairs to the upper deck.

In those days, the top decks of London buses were the preserve of smokers.

Hard to imagine today, but the seats were filled with people puffing away on cigarettes and, in some cases, even pipes.

It may have been misty outside, but inside the bus could be a real peasouper of a fog, if you were sitting upstairs.

Tim and Roy gratefully settled into their seats and each lit up a cigarette, something they hadn’t been able to do in the wet outside.

The bus passed a poster of the Shultz cartoon character, Charlie Brown.

The poster had a caption that began ‘Happiness is…’, taking this in, Tim settled back in his seat and said ‘Happiness is a dry cigarette on the top deck of a 134 bus’.

The pair soon realised that if they changed what Tim had said to ‘Happiness is a cigar called Hamlet’, and put a suitably funny, but unfortunate event or situation in front of that line, they might have the campaign they’d been looking for.

And so it proved.

Well, that’s one version of how Tim and Roy did Hamlet, the generally accepted one, the official one, if you like.

But there is another story.

Vernon Howe, one of CDP’s senior art directors told a friend of his, Steve Harrison, that Tim Warriner had been trying to sell the idea of ‘Happiness is…’ to any client who’d have it. It just so happened that Hamlet bought it.

You can choose which version you prefer.

I know which one I do.

The first commercial, filmed in glorious black and white, showed a man in a hospital bed with his leg in traction, happily puffing away on a Hamlet cigar.

Tim and Roy did others: a music teacher, played by Patrick Cargill, whose pupil only plays the piano tunefully when his teacher smokes a Hamlet.

And ‘Launderette’ – yes, launderette – more or less the same idea used by Bartle Bogle Hegarty for Levis more than a dozen years later.

Instead of casting a hunk in the form of Nick Kamen, as Levis did, this being Hamlet, Tim and Roy filmed a meek looking city gent, complete with bowler hat.

Of course, the Hamlet campaign wouldn’t be the Hamlet campaign without the music, and we have Colin Millward to thank for that.

Colin had served in the Royal Air Force. Shortly after the end of the Second World War he was posted to India where he lived in a hut for six months. The previous occupant had left Colin a gramophone, but only one record.

On one side of this disc was Debussy’s ‘Clair de Lune’. On the other, Bach’s ‘Air on the G String’.

Colin remembered the Bach music and suggested that it should provide the commercials’ soundtrack.

In 1959, a French Jazz Musician called Jacques Loussier had formed the ‘Play Bach Trio’. They released a series of albums under this name, featuring the simple combination of piano, bass and drums performing improvised versions of Bach.

Amongst these was a jazz version of ‘Air on a G String’.

OTHER HAMLET STUFF.

1. Facts.

The cigars come individually wrapped in cellophane. In many commercials, the cigar is seen in close up being removed from the pack with the cellophane intact, then in the actor’s mouth with the cellophane removed.

Nobody seemed to notice this continuity error, which was intentional.

The end line changed subtly in the early eighties to satisfy regulators who insisted that ‘from Benson and Hedges’ at the end of the line was selling cigarettes, rather than Hamlet.

The words were dropped so that the end line became simply ‘Happiness is a cigar called Hamlet, the mild cigar.’

The commercial created in the shortest time was ‘Crash of ‘87’ written by Adrian Holmes and John Foster.

From conception to broadcast took just over 24 hours.

The longest Hamlet commercial was ‘Photo Booth’ at one minute long.

The vast majority of Hamlet commercials were only 30 seconds in length.

One Hamlet commercial, ‘Sidecar’, was written by a member of the public.

John Salmon oversaw the filming.

John Carson voiced all Hamlet commercials, except those shown in The Republic of Ireland, which used Fergus O’Kelly because he was a member of Irish Equity and John Carson wasn’t.

John Ritchie, who at that time was the account handler on Hamlet, was duly despatched to Paris to pursuade Jacques Loussier and his trio to record a 30 second version for use in the commercials.

Ritchie tracked down Loussier to his apartment on the outskirts of Paris.

Loussier wasn’t home so Ritchie camped outside for three days until the muscian turned up.

To keep himself going, Ritchie had been popping uppers, so when he finally met Loussier he was hyper, unable to sit still, and conducted the negotiation with Loussier while running around the room.

Nethertheless, he was successful and Loussier agreed on a £1,000 fee.

As I struggled to explain why the Hamlet music is so apposite, I sought the help of a musician who was a friend of mine, the late Mike Townend.

Mike had worked with people like Smokey Robinson and Burt Bacharach, so he knew what he was talking about.

As well as pointing out that the correct title of the piece is ‘Air from Suite No 3 in D Major’, he told me to study Bach’s original version.

He said it is typical of Bach’s early work in as much as it builds tension, then moves towards a release, or ‘climax’.

When I heard this, it sounded just like the structure of a Hamlet commercial – tension in the form of an unfortunate event or situation, followed by release as the protagonist smokes the Hamlet – so that may be why the music is so apt.

That, plus the fact that it’s a damned good tune, of course.

Frank Lowe, managing director of CDP in the seventies, tells a story about Jacques Loussier and the music.

“The music track was getting worn out so we had to go to Paris to re-record it with Jacques Loussier – John Richie, the TV producer and I went over and met with Jacques who played it several times… each time it was different and none of them were quite like the original.

I had forgotten that jazz musicians normally extemporise differently every time they play any piece of music. We went to lunch at a very nice brasserie and during the lunch I challenged Jacques that he couldn’t play it in exactly the same way as the original – nonsense he said (or the French equivalent) and went back and played it exactly as we wanted it – whereupon we dashed back to London.”

Tim and Roy’s legacy left those of us who worked in the creative department of CDP a lot to live up to.

Year after year, teams of writers and art directors received briefs to write Hamlet commercials.

Some of these follow up commercials came to be regarded as classics and became popular with the general public.

And, as with the repertoire of a well-liked recording artist, everybody has his or her favourite.

A film that many people cite, including Frank Lowe is ‘Bunker’.

This is the commercial that doesn’t show an unfortunate golfer whose ball has become lodged in a sand bunker.

Neither does it show the cigar, nor the pack. All we see is smoke rising from below the rim of the bunker as the unseen golfer consoles himself with his Hamlet.

By the time this commercial was made in 1980, the campaign was so well established that the creative team, Rob Morris and Alfredo Marcantonio, and the director, Paul Weiland, could get away with this cavalier approach to the client’s product.

Interestingly, when I spoke to Mike Townend about the music, this was one of the two Hamlet commercials he mentioned spontaneously.

The other was what is undoubtedly the public’s favourite, Gregor Fisher in the photo booth.

What is undeniable is that this commercial is an outstanding piece of advertising, the brainchild of the creative team involved, Rowan Dean and Gary Horner. They spotted a sketch on a BBC programme called ‘Naked Video’.

In this sketch, ‘Baldy Man’, a character created by comedian and actor Gregor Fisher, posed in a photo booth, only to be thwarted in his attempts to get the perfect photograph by series of mishaps culminating in the stool he is sitting on collapsing beneath him.

Rowan and Gary immediately saw the potential for turning it into a Hamlet commercial, which they duly did.

There’s no getting away from the fact that it worked – and promptly became the most memorable Hamlet commercial ever.

Not for the first time, the Hamlet campaign had proved itself to be unstoppable.

As Peter Wilson, a marketing manager at Gallaher in those days, says ‘the advertising for Hamlet was incredibly successful.

It built the brand into the best-selling cigar in the UK market. Four out of every ten cigars sold was a Hamlet’.

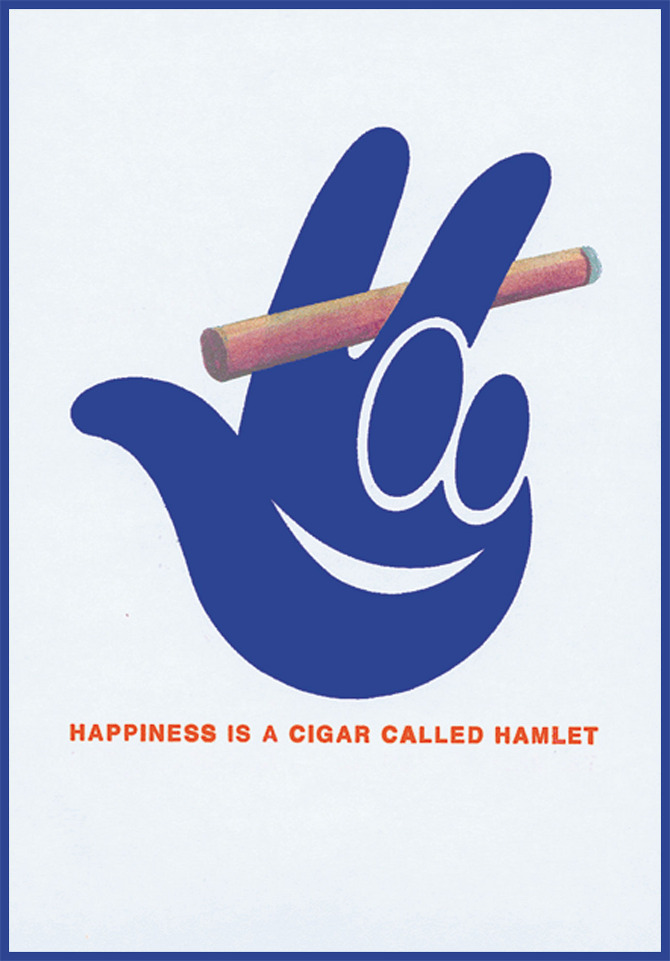

Were it not for the European Union or, as it was then, the EEC, who banned all tobacco advertising in the 1990s, it’s tempting to think that the Hamlet campaign could still be running today.

As it was, the campaign took a dignified bow, and left our screens for good at the end of that decade, 25 years after it had begun.

In all, CDP had created over 80 commercials, every one of which was a funny, beautifully told story of disaster followed by the happiness of smoking a Hamlet cigar.

I wonder if back in 1964, those two blokes sitting in a dingy office, staring at a blank sheet of paper realised what a wonderful monster they were on the verge of creating.

I doubt it. In all probability, they saw it as just another day’s work, albeit a pretty good one.

2. Other commercials.

4. Mike on ‘Venus De Milo’, (1976).

The summer of 1973, Paul Smith and I were a couple of months into the job that was to have a profoundly beneficial effect on our lives: working as a creative team at Collett, Dickenson, Pearce.

We’d got our first ad approved, a full page black and white effort for the Salton Hotray, a device designed to keep food warm until the person hosting a meal wished to serve it.

Hence our ad’s headline: ‘Eat when you’re ready, not when the food is’. We’d also been given Silk Cut cigarettes to look after.

Something that the account director on the business, Colin Probert, was a bit miffed about at the time, as he considered us to be too young and inexperienced to write and art direct the many ads demanded by such a large piece of business. (We went on to have a great working relationship with him.)

But, so far, we hadn’t been asked to write any commercials. Then a brief for Hamlet arrived in our office.

Hamlet was the agency’s most famous campaign. Not only was it successful at generating sales, it was also popular with the public.

So much so that members of the public often sent in ideas for scripts.

On one occasion, the idea was good enough to be used and a fee sent to the author.

Still, for a young creative team faced with their first TV brief, the prospect of writing a Hamlet script remained daunting.

On the face of it, Hamlet commercials are simple: something goes wrong, a Hamlet cigar is smoked, and all’s right with the world.

But try writing one.

Oh, it’s easy enough to find a situation that goes wrong. But to dream up one that’s funny as well, that’s the difficult bit.

Especially after you’ve watched every Hamlet commercial that’s ever been made, as Paul and I did before we began work. If we didn’t know it before, we knew it now. There was a lot to live up to.

We spent days writing scripts, or rather not writing them, as we searched for an idea that would tickle the funny bone of Vernon Howe, then our creative group head, John Salmon, the creative director and finally, Frank Lowe.

In the case of all TV scripts that passed through the agency, Frank was God on High.

Nothing was allowed out of the agency without his signature, plus those of John and Vernon and that John Ritchie, the account director.

Eventually we managed to tease from ourselves a number of scripts that we considered good enough to show Vernon.

But two stood out. One depicted a sculptor putting the finishing touch to a piece of his work, only to ruin it; the other was about a young man looking through a beach telescope whose money ran out just as the pretty girl he was ogling began to remove her bikini top.

Vernon liked both, but suggested that the sculptor might be funnier if he was creating a famous piece of sculpture like the Venus de Milo.

That was it, the Venus de Milo. Why didn’t we think of that? We could show the statue complete with arms. The sculptor would stand back to admire his work. He spots a small imperfection, takes hammer and chisel to one of the arms, and lo and behold, knocks it off. We’re left with the Venus de Milo, as now we know her. Bingo! We now had two great scripts.

Or so we thought. There was still the agency approval system to get through.

John Salmon had gone on holiday, leaving Geoff Seymour to approve all TV scripts, while Neil Godfrey and Tony Brignull were in overall charge of print.

John usually did both. This meant that our two Hamlet scripts landed on Geoff’s desk for approval, instead of John’s.

Almost immediately, Paul and I were summoned to Geoff’s office. He told us he liked the Venus de Milo idea, but thought that the beach telescope script was off strategy.

Now the Hamlet strategy can be summed up in one word: ‘consolation’. And the guy who is robbed of the chance to see the bikini-clad girl disrobe certainly needed to be consoled. So we were confused by what Geoff had said.

But we had two scripts on the table. Geoff asked us how many we needed. It was just one.

So Venus de Milo went forward and Beach Telescope didn’t.

I had never been involved in the production of a commercial before and Paul had only been through the process once. So when the approved script came back from the client and we were asked to make it we didn’t really know what to do.

But we needn’t have worried. Barry Mathews was then head of TV production and he oversaw a team of brilliant producers.

Almost immediately, one of these turned up in our office and asked us who we’d like to have to direct the film. Paul and I looked at each other. We had no idea. So our producer suggested we look at some show reels to help us decide.

Looking at show reels is a great way to while away a couple of hours. It requires no real work and if you are watching the reel of one of the better directors, it can be highly entertaining. I have to say, though, it did help with our decision.

We chose Sid Roberson and a meeting was set up to meet him.

Sid had displayed a great sense of humour in the work we’d seen and the man himself didn’t disappoint.

Among other things, he was famous for playing the archer in a series of Strongbow cider commercials that were then running on TV.

His biceps were the size of rugby balls and he had a sense of humour to match.

The shoot was scheduled to take place at the old Lee Studios in Ladbroke Grove shortly before Christmas.

As it was our first CDP shoot, Geoff Seymour was sent along to the studio to watch over us.

But we weren’t the ones who should have been watched over.

Sid had hired as his director of photography somebody who was often referred to as the ‘Prince of Darkness’.

We soon found out why.

The filming went by swimmingly, as Sid got shot after shot into the can.

Then, around six o’clock, when there was just one shot left to do, the Prince of Darkness sidled up to Sid.

His Highness had just realised that he’d shot the entire film using the wrong exposure for his lighting. This meant that all the footage that Sid had shot was useless. We had no alternative but to film the whole commercial all over again. Imagine how Paul and I felt.

Our first-ever CDP commercial and before we’d even finished it we were going into a re-shoot.

Not exactly auspicious.

5. Mike on ‘Telescope’, (1980).

Monday July 16th, 1973 was the day that Paul Smith and I started at CDP.

We’d arranged to meet at Tottenham Court Road tube station and arrived at the agency on the dot of nine, the agency’s official start time. Sergeant Hambleton, the Corps of Commissionaires doorman, gave us permission to go up the fourth floor, home to the creative department. Nobody was there. We didn’t quite know what to do, so we wandered around the empty offices looking at the work. The first office we walked into belonged to Tony Brignull. There, staring us in the face was a pile of concepts for Dunn & Co, the men’s clothier. The topmost concept, ‘Success doesn’t always go to your head’, showed a triptych of three men’s waistlines, one slim, one starting to develop a fat stomach, and one with a stomach that had already developed. We looked at the second ad in the pile: ‘The life of a designer for Dunn and Company is one of continual self-restraint’. We couldn’t look any further, we were terrified. If this was the standard of work the agency was producing we’d be lucky if we lasted a week. As it happened, we lasted 14 years.

As if this wasn’t bad enough, the special effects didn’t work as well as we all hoped. Venus de Milo’s arm was supposed to be dislodged by the merest tap of the sculptor’s hammer on his chisel. In the event, it took a huge whack from the actor before the arm fell to the ground. As you can imagine, this rather spoiled the joke because it looked as if the sculptor was deliberately trying to smash off the arm. Eventually, we shot a take that didn’t look too bad and we moved on. But when we saw the rushes the next day (remember, in those days there was no video playback) the shot just didn’t work. Being inexperienced, Paul and I allowed the shot to go into the cut and showed the cut in the agency. Both Vernon and John Salmon spotted it immediately. John also asked if we had filmed anything after the sculptor lit his Hamlet where the actor looked at the one remaining arm as if to consider removing that one to match the fallen arm. Luckily, we did have such a shot and we cut it into the commercial. But there remained the question of the pivotal piece of film in which the sculptor accidentally removes the arm.

There was nothing remotely useable in the footage we had shot, so John Salmon decided that we should set about re-filming that part of the commercial.

The way this sort of thing was undertaken at CDP was to piggyback the re-shoot onto another CDP shoot if it was a short sequence like this.

This was exactly what happened in this case. I can’t remember which shoot we invaded, but rather incongruously the sound stage had a flat (a wall used as a background) that represented the studio of an ancient Athenian sculptor, and three flats that made up the walls of a modern kitchen.

The special effects boys had done some work and this time the arm severed itself without the actor having to take a lunge at it.

The shot safely in the can, we presented the finished film to the agency.

We asked our producer what would happen if Frank Lowe didn’t like it.

She assured us he’d like it, it was a good film. But if he didn’t, she’d give him a blowjob, then he’d love it.

As it happened, she wasn’t called upon to go beyond the call of duty.

Frank loved the film anyway.

So did the public.

And so did the awards juries.

Our first CDP commercial and our first Hamlet commercial safely on air and on our show reel.

What a relief.

Now let’s fast-forward to 1980.

Here we are, still working at CDP, only now at Euston Road instead of Howland Street.

We occupy an office on the 15th floor with glorious views over London.

The only downside of our marvellous location is that the next room to ours is John Salmon’s private toilet.

But that’s a small price to pay to be near John, who was now the agency’s managing director.

However, being close to the boss didn’t mean we could put our feet up.

Brief after brief was landing on our desks. We had never been busier.

One of these briefs was awfully familiar: write a 30 second commercial for Hamlet using the Happiness end line.

So the Hamlet campaign had made its way round the creative department back to us again after an interval of seven years.

In the meantime, many more great commercials had been made. For example, Rita Dempsey and Phil Mason’s tennis commercial, which showed John Bluthal in a neck brace vainly attempting to watch a match at Wimbledon, unable to turn his head from side to side to keep track of the action.

And Paul Weiland and David Horry’s robot commercial, made to coincide with the screening of Star Wars, where a C3PO type robot emerges from the production line with his head on backwards.

Yes, we were faced not only with the same brief as seven years earlier, but also the same problem.

Write a Hamlet commercial that’s so unexpected, yet so funny, that it stood a chance of getting made.

Now if you’re in advertising you will know what I am about to tell you.

Creative people never throw away a good idea. When it gets turned down, they keep it and try and use it again, usually for a different client or even in a different agency.

John Webster, creative director of Boase Massimi Pollitt and probably Britain’s best ever writer of TV commercials, did this with a Volkswagen commercial that featured a driver being annoyed by a constant squeak as he drove his sleeping wife through the countryside.

He stops at a service station and puts a drop of oil on his wife’s earring, end of squeak.

John had apparently written this idea for British Leyland years before when he was at Pritchard Wood but the client had rejected it.

Probably quite rightly, as in those days British Leyland cars were full of all sorts of squeaks.

Another example is the Carling Black Label campaign, ‘I bet he drinks Carling Black Label’, which was originally written for the Milk Marketing Board as ‘I bet he drinks milk’.

And guess what? Paul and I had never thrown away our beach telescope script.

Geoff Seymour had long since left the agency. John Salmon had never seen the script, because he was on holiday. Vernon, too, had moved on to other pastures. He was now a successful film director.

We got out the script and looked at it. Well, the paper it was typed on may have looked faded and dog-eared, but the idea was as shiny as ever.

It still made us laugh.

So we wrote it out again and had it re-typed.

We didn’t even have to do what most people do, change the name of the product.

The only change was the date at the top of the headed script paper.

This time it sailed through the approval system, without a mention of strategy from anyone.

One or two people may have been astonished at the speed at which Paul and I turned round the job.

But if they were, they never showed it. It went to the client and straight into production.

We chose Paul Weiland to film the script.

Paul had been working as a commercials director at the Alan Parker Film Company and had recently left to start his own firm.

Before that, he was a fellow copywriter at CDP. At one of our meetings with Paul, he had suggested that we needed something to lead the guy looking through the telescope to discover the girl as she took her bikini top off.

What about a sailing boat, somebody suggested. No, we all decided, that would take too long.

In the end, we hit on the idea of a water-skier. A water-skier would be able to travel faster through frame as the guy with the telescope tracked his progress.

At the end of this tracking sequence, we could have the guy do a double-take with the telescope, then settle on the girl undressing just as his money ran out. Cue Hamlet moment. Perfect.

If special effects are unreliable, try using a stunt man. Particularly, one who assures you he can water-ski.

One thing you learn is that when people at casting sessions tell you they can do something, there’s a good chance they can’t.

Can you drive? Yes. It’s a stone cold certainty that they don’t have a licence. Can you ride a horse? Yes, of course.

They’ll fall off at the first opportunity, that’s assuming they can get on the bloody thing in the first place. Can you water-ski? You guessed it.

We chose as the location for the shoot Durdle Door in Dorset. Apart from alliteration, it provided a perfect place to film the commercial.

And we were lucky with the weather: a beautiful summer’s day with blue sky from horizon to horizon.

All went well until the time came to film the water-skier.

A mask was put over the camera lens to simulate the view through the telescope. Paul Smith, Paul Weiland and I were beside the camera, which was sited on top of the cliffs. Far below, the water-skier was bobbing up and down in the sea, awaiting the command via walkie-talkie to do his stuff.

‘Turn over’, the instruction to start running the film through the camera, came from the ‘first’, the assistant director.

The camera operator shouted ‘Speed’, the reply when the film reaches the correct velocity.

‘And action’ yelled Paul Weiland into his walkie-talkie.

But there wasn’t any action.

In fact, there wasn’t much of anything. Just the water-skier being dragged a few yards through the briny, spluttering out mouthfuls of water, and losing his skis in the process.

This scene was repeated a couple of times before Paul Weiland became frustrated and sent his first assistant director down to find out what was going wrong.

What was going wrong was quite simple. The water skier couldn’t water- ski. In fact, he’d never water-skied before in his life. He had hoped to bluff his way through it and somehow or other get the scene filmed. But, of course, this was foolhardy. In a belated act of wisdom, he chose to throw in the towel. It was either that or drown.

We may have been unlucky with our choice of water-skier, but we were extremely fortunate in our choice of focus-puller, Trevor Brooker.

Not only was Trevor a dab hand at his job, he happened to be a keen amateur water-skier. So he took over the part.

Paul Weiland filmed three perfect passes of our new water-skier, who showed no signs of faltering or, indeed, of drowning, and moved on to the next shot.

The film was in the can long before sun down.

What these two stories illustrate – apart from the fact that a film shoot is rarely a straightforward endeavour – is that perseverance can take many forms.

If at first you don’t succeed, try and try again, was CDP’s ethos.

Try again to have a better idea.

Try again to think of a better way to film that idea.

Never give up. In this case, Paul Smith and I clung to a script for many years before the chance came to use it again.

Cheating? Maybe. But why struggle to write something else when you have something good already – something that went on to win a gold award at BTA and flew into the D&AD annual.

Save your energy for where it’s needed. For all the other briefs for all the other products you’ve never worked on before.

Were he still alive, I like to think that John Webster would agree.

I guess Mike has approached Sir Frank Lowe.

Thanks again Dave. Would be great if the book could show the actual commercials, ‘stead of storyboards or a YouTube link.

Like in Harry Potter? Don’t think that tech is with us yet Robin, but I’ll check. Dx

Dave, this is so great. Your blog is a text book on advertising. Everyone should read it.

Thanks George, very kind, particularly coming from one of my favourite bloggers.

(Sorry for that ‘u’, I know you guys hate that.) Dx