We’re smack bang in the middle of the age of collaboration.

Any press release for a creative hiring now contains that reassuring phrase ‘Known for being collaborative’.

(To me it always reads ‘We’re pleased to announce we’ve finally found a creative who will listen to us’.)

The feeling the team had creating the work is as scrutinised as what they created.

But collaboration means different things to different people.

For most of the team it conjures up enjoyable meetings on astro-turf where everyone is contributes, feels validated and no-one dominates.

If your role in the team is to come up with the ideas for the meeting, being asked to be collaborative is like being asked to ‘amalgamate everyone’s suggestions into your idea whilst maintaining smile.’

It’s not that as creatives we are against collaborating, our job means we have to collaborate than any other department.

But being seen to be collaborative is not the same as collaboration.

To be seen to be collaborative requires you to accept a percentage of suggestions from the attendees, regardless of their merit.

About 1 in 5. (Any less than that and you’ve no chance of the word collaborative turning up in any future press releases.)

But in my experience the best ads are the result of one person leading the charge, steering the ship, making the calls.

They invite suggestions from everyone, which is collaborative, in that they they’re like oxygen, BUT, they decide whether those suggestions are used or binned based on THEIR vision.

It’s hard to do, certainly harder than ‘being seen to be collaborative’, (where you’ll argue less, think less, justify less, be more popular and, if the ad turns out to be a dud; you won’t have to carry the can.)

Consequently, few have the self-belief to take responsibility for the end result.

Frank Budgen did.

There are eight thousand words below, written by those who worked with him.

Collaboration isn’t one of them.

He shot an a Mercedes ad for my agency, reports from the shoot were ‘He doesn’t argue or disagree, he listens politely, then does whatever he wants to do…it’s as if you’d never had the conversation.’

Mark Denton describes Frank’s biggest asset as ‘his ability to ignore everything agencies and clients say, without ever getting sued’.

Another said ‘we spent the first half of the first day shooting something no-one had ever discussed…and ended up not being used.’

Frank wasn’t a smiley, collaborative type.

This post wouldn’t be be anywhere near as good if he were.

Enjoy.

CREATIVE.

“Did I discover one of the most talented directors of TV commercials of his generation?

Probably not, but I may have inadvertently sent him on his way.

I met Frank just after he graduated from the advertising course at Manchester under the brilliant tutelage of John Driver, the famed head of the advertising course.

I am going to guess at a year, it could’ve been 1976.

His girlfriend at the time was Joanna Wenley, who was still at Manchester and in her final year.

Joanna was on work experience under the eye of my writing partner John Kelley who was group head at CDP. She’d been partnered with another budding creative; Paul Weinberger, also fresh out of university, with a degree in Anthology.

Joanna asked John Kelley and I if we would meet Frank and take a look at his book.

To be honest, I can’t remember what was in it, but it was obviously good enough for us both to recommend him to our old boss Tim Delaney, who Creative director of BBDO at the time.

If my addled memory cells are correct, I think I called up Tim’s secretary and made an appointment for him and even wrote a letter to Tim suggesting it would be foolhardy of him not to give Frank a job.

Mr Delaney did and to my knowledge Frank blossomed into a very good copywriter.

Over the years our paths crossed at the usual parties and BBDO reunions, which in those days were events in themselves.

Then, in 1983, I made the decision to make a career as a commercials director and joined The Paul Weiland Film Company.

Starting out as a director isn’t a wise decision if you’ve never even attempted to direct anything before.

I hadn’t. (Arrogance or stupidly? In hindsight, a bit of both.)

Who the fuck is going to give a film to someone who hasn’t ever made film?

Frank Budgen.

He and his art director Bill Gallagher gave me a script.

It helped that the pair were working at BMP, considered to be the best agency in town at the time.

My career got a kick start.

Thank you Frank and Bill.

My relationship with Frank didn’t end there as a few years later he joined me at Weiland’s as a director.

Now what about the late Mr Budgen as a rookie film maker?

Was he the assertive, decisive and efficient leader that it takes to be an unparalleled success as a director?

Nope.

He was none of those things. He was a producers nightmare.

In his early days, the morning after his shoots back at the Weiland’s office were hilarious.

“How did it go? I’d ask whoever was the producer was on his job.

“A f***ing nightmare. Literally, we didn’t wrap until midnight.” would be the normal reply.

Of course, myself being a goody two shoes at the company, I was a paragon of shooting efficiency, always finishing on time and on budget.

Producers loved me, as did Paul Weiland, I began to think that dear old Frank won’t last long.

That was until I began see the edits of his films.

Pure brilliance.

Frank was in another league.

From then on I could gauge the awards Frank would be taking & shaking based on how much the producers moaned about his supposed short-comings as a director.

Finishing at eleven was worth a silver arrow at the British Television awards.

Midnight, a silver at D&AD.

Early hours of the morning would guarantee him a gold in whatever the awards system.

Frank had a bit of a Vampyric existence at Weiland’s. He only came into office in the evening. In fact they used to assign a runner to stay with him until he went home. (This was called ‘Frank duty’ by the youngsters.)

When he did come in it was normally at the time leaving the office to go home.

I’d see Frank standing at the reception desk reading the scripts that had began to flood from agencies.

I once asked him if there was an in and out tray for those he fancied and those he didn’t.

More often than not he would reply that there was only an ‘out’.

This is the Frank I knew.

To me he was quietly spoken and when he did speak I got the feeling he was raising a voice that didn’t really want to heard.

I imagine he was that kid at school who didn’t say much but was always be top of the class.

No change there then.”

– JOHN O’DRISCOLL. (Creative & Director)

Saatch & Saatchi.

Purina.

British Leyland.

“Frank and I were teamed up at Saatchi & Saatchi, Jeremy Sinclair was our Creative

Director and was instrumental in teaming us up.

Frank had been working to Peter Mayle the then Creative Director at BBDO, I had been working to Norman Berry Creative Director at DPBS.

Frank was a very talented writer, quiet with a dry sense of humour, and most of all very determined.

Frank had an enthusiasm for TV advertising, less so for press and poster.

We worked on British Rail, Schweppes, British Caledonian Airways, The Sunday and Daily Mail, , Haymarket Publishing, N.S.P.C.C. and Vidor Batteries.

One brief was to advertise ‘The Ideal Home Exhibition.’

We decided to use the string puppets Bill and Ben ‘The Flower Pot Men’.

Weed taps on the Ben’s pot, it cracks and a large chunk falls to the floor.

Ben says ‘Blolly Flollaplop’ (Bloody Flowerpot).

Ben pops up and asks Bill when does the Ideal Home Exhibition start?

Then the voice comes in and says ‘For new and money saving ideas to improve your home visit the Ideal Home Exhibition.

We managed to obtain the original puppets from the BBC, then painted the strings white, filmed in B/W and hired the actor and actress who voiced the BBC series.

It became our first TV ad to be published in The D&AD Annual.

Frank had a plan to try as many film techniques as possible to further his knowledge, this

became obvious as time went on.

Jeff Stark became our Group Head when the Group system was introduced in Saatchi & Saatchi.

Frank and Jeff lived in Putney and became very good friends.

Late one afternoon, we went into Jeff’s office to take a brief for the Daily Mail

newspaper.

Jeff then spent the next four hours practising his Comedy Store routine on us…..……….eventually we produced an ad around 11pm that evening.

The account man came in to take the ad to present, he took one look and said ‘I don’t understand it?”.

He re appeared an hour later saying ‘I’ve sold it, I still don’t understand it’.

(There was more trust between Client and Agency back then.)

After 3 years at Saatchi & Saatchi we joined BMP.

At our interview with John Webster we heard a cheer go up down the corridor, John turned to us and said ‘Someone has got an ad through’.

Frank was in his element, working three doors down from John Webster. (The Potter)

However, our first real success was a press ad for Fisher Price.

The photo was of one boy to the right of the page (he had a face like a baked bean) his arms folded with a broad grin on his face.

Headline- Which one of these three kids is wearing Fisher-Price anti-slip roller skates?

This won a D&AD pencil.

We then shot a TV for Dime Bar directed by John O’Driscoll

end-line Dime Bar; ‘Sounds just like an avalanche’.

We then worked on the ‘War on Want’ charity’

The production budget was £000.00.

We decided to use photomontage visuals taking our inspiration

from John Heartfield, who produced anti-Hitler posters in pre-war Germany.

The copy was hand set in the typographer Dave Wakefield’s garage, where he held a collection of metal and wood typefaces.

We discovered we could use stock shots for free if we took copies on the stat machine. The first 3 ads took an age to accomplish.

Tony Davidson, Kim Papworth, Andy McKay and Colin Jones eventually helped us produce another six ads.

We were told not to waste too much time on these during normal working hours, so we

worked evenings and weekends.

Next we were asked to work up a series of TV ads for John Smiths Bitter.

Frank made his directorial debut with one of the series titled ‘True Love’, with the

end line – ‘For Incurable Romantics’.

‘Song and Dance’ won The ITV Commercial of the Year, the remainder won 4 gold arrows and 2 silver arrows. (The series was produced and filmed by Park Village.)

For the next project, Cellnet mobile phones, we filmed time-lapse footage, the idea was influenced by the feature film Koyaanisqatsi.

I remember Frank staggering in one morning looking more pale than normal, having spent the whole night freezing, perched on top a tall building watching a camera film a time lapse panoramic view of London.

By this time it was obvious, Frank’s ambition was to become a Film Director, so we decided to split up.

I partnered John Pallant and we left to work for Paul Arden at Saatchi & Saatchi,

Frank partnered Peter Gatley for a time, before he went full time as a director

at The Paul Weiland Film Company.

A couple of years before I worked with Frank my brother had contracted Leukaemia.

In later years, Frank would contact me occasionally to inquire about my brother’s treatment for Leukaemia hoping to learn any new research developments.”

– BILL GALLACHER (Creative)

Ideal Homes Exhibition.

Boase Massimi Pollitt.

Dime Bar.

“I met Frank on my first day in advertising.

I’d just started at BMP, Frank had already been working for a year at BBDO. Jo Wenley, another BMP junior, invited us for lunch.

He was modest and quietly-spoken, and though keen like us all to make his mark, did not seem to be in such a hurry.

When I said that I was aiming to be in the D&AD book by the following year, he thought I was getting a bit above myself.

Frank went at his own steady pace, quietly absorbing everything he could from everyone, and carefully choosing his opportunities to shine.

He went on to Saatchi and then BMP, while I went to CDP and GGT, and then back to BMP, joining him and a very lively creative department.

And it was at BMP – and particularly working with John Webster – that Frank really seemed to flourish. The awards followed quickly.

He directed several commercials while he was a writer, but resisted moving to a production company for some time.

I remember saying to him, didn’t he just want to get on with it and shoot as much as possible as quickly as possible? But he said he wanted to find the right project.

When he finally did move, and to one of London’s best production houses, he continued to be extremely selective. If he didn’t think he could do something new with a script, he would pass.

Luckily, for Matt Ryan and me, at Saatchi by then, one of the ideas that appealed to him early on was ours. It could not have gone better – with his total focus and commitment, it exceeded even our expectations in all the festivals.

After that, every choice he made was a good one. At the peak of his success, I think he was shooting just three or four films a year, but all outstanding.

Some years later, I bumped into him on a Sunday afternoon – he said he’d just spent a couple of hours with Jerry Bruckheimer’s team who’d flown in from LA to persuade him to shoot a feature film – it was Con Air.

He said he’d turned it down.

I’m sure it was one of many.”

– JOHN PALLANT. (Creative)

Knorr.

Derbyshire County Council.

“Frank was an enigma.

I first met him when he worked alongside Bill Gallacher at BMP. They were then a senior team who sat opposite myself and Kim Papworth, the juniors. They were famous for not producing much, but what they did, was quality.

We’d often show them our work, Frank seemed shy and indecisive, but had moments of real clarity. I remember him telling us to simplify our idea for Karvol by ‘just using the sound of a baby with breathing difficulties’. It made the ad stand out far more.

On another occasion, for the charity War on Want, he told us to write every line of copy as facts, rather than flowery copy, it improved it, giving the ads a sense of urgency.

Although officially a copywriter, he stored visual references and took loads of photos.

Frank studied on the same advertising course as I did (few years earlier!) at Manchester Polytechnic, but someone told me that he spent as much time in the photography department as he did on the advertising course.

This balance of a writers discipline and experimental photographic eye made him stand out.

Like many of us, he learnt and worked with the great John Webster; Storytelling was drummed into him.

Their Guardian ‘Skinhead’ idea came from a photograph, you could tell that Frank had a big part in it as there was no furry animal or music track in sight.

Frank was cautious.

He started directing whilst still at BMP and his directing debuts were both single pull back to reveal camera moves, one for the award winning John Smiths ‘Arkwright’ campaign.

He then directed some Knorr commercials based on European cinema (he was always more art house than populist) before leaving to direct at Paul Weiland Films.

Every producer I’ve spoken to about working with Frank pulls their hair out in frustration, admiration and love.

He found it difficult to make any decisions until his eye was behind the camera. He was forever changing his mind, but whilst he may not have always conveyed why he was doing what he was doing, inside, his mind was working overtime, always with the story in mind.

When Tony Kaye started breaking all the rules of directing I think it influenced Frank.

As a creative he’d worked with Tony on a Southern Comfort ad.

Shot in New Orleans, Tony went off-piste from day one, shooting a burning house that wasn’t on the storyboard, but that made him ‘feel’ something.

This freedom to express yourself through film, in a non linear way, excited Frank.

He moved to set up Gorgeous Films with Chris Palmer and Paul Rothwell and the rest is history.

I was lucky enough to work with him on a Pepe Jeans commercial, his openness to try new things, his references, his pain and desire to do something new, were inspiring.

He may not have come across as competitive, but trust me, I played football with him for years, despite his gangly frame he was fully committed and irritatingly good. Same with tennis. Same with all sports.

I think we are all part ourselves, part the people we meet and part the interests we choose.

Frank was a wonderful combination; part introvert, part writer, part storyteller, part photographer, part competitor, part perfectionist, part film-maker. Because of this, his ability to take someone’s half-baked idea and turn it into gold dust was second to none.

Whatever he put his mind to he was never satisfied, forever changing, it was part of his genius.

I hope he is still driving some producers crazy in another life.

He is sorely missed in this one.”

– TONY DAVIDSON. (Creative)

War On Want.

“Landing a job at BMP in the mid-1980s was like winning the lottery.

“Landing a job at BMP in the mid-1980s was like winning the lottery.

What a creative department.

Kim Papworth and Tony Davidson. Nick Gill and Alan Howell. Jo Wenley and Patrick Collister. Dave Buchanan and Mike Hannett. Colin Jones and Jane Simmons. Rob Oliver and Roger Holdsworth. Alan Tilby and Paul Leeves. John Webster. Ian Ducker and Will Farquhar. Rooney Carruthers and Larry Barker. John Pallant and Pete Gatley. Andy McKay and Richard Russell. Mike Durban and Landsley Henry. Julian Dyer and Dennis Willison. Kevin Kneale and Mike Elliot. Alan Curson and Simon Hunt. Gary Denham and Dave Watkinson. Sean Toal and Mitch Levy. And, sitting quietly in an office with Bill Gallagher, Frank Budgen.

It was the best advertising education anyone could have.

I learnt from all these talented people.

But I probably learnt the most from Frank.

His work had a kind of brilliant simplicity.

Like the man himself, it wasn’t flashy or attention-seeking.

It just seemed effortless.

When BMP won the Fosters lager account, the whole department set to work writing snappy one-liners for the brand spokesman, Paul Hogan, who was fresh from his starring role in Crocodile Dundee.

Frank wrote a script where Hogan didn’t say a single word.

It was the best of the bunch – and the only ad in the campaign that got into D&AD.

As John Hegarty would later say: when the world zigs, zag.

Frank taught me that everything was an opportunity.

Faced with an unpromising trade press brief for Fisher Price roller skates, Frank and Bill created an ad that made people laugh out loud when they saw it. (For a print ad, that’s pretty good going.)

Silver pencil at D&AD.

BMP won The Guardian account in 1985, and, for a couple of years, created some very respectable work.

Then Frank worked on it, and wrote what, for me, is one of the best ads of all time: Points of View.

Compelling. Unarguable. Brilliantly simple. All in 30”.

Frank knew exactly how he wanted it to look, too.

I remember him showing us the Don McCullin photograph of British soldiers running down a street in Derry, with local women taking cover in the doorways.

Points of View was such a perfect demonstration of what made The Guardian essential reading, it was hard to see how you could write another commercial for the brand.

(Interestingly, the next great Guardian ad, nearly 30 years later, borrowed the same endline: The Whole Picture.)

Yet somehow, Points of View only won a silver at D&AD.

So it probably caused more than a few ads after that to miss out on a black pencil, too.

“Well…” jurors would say, “if Points of View didn’t get black…”

Frank reinvigorated the John’s Smiths Yorkshire Bitter campaign, co-writing the scripts with John Webster and directing one of the ads himself – his first as a director.

Again, it was beautifully simple. Just a pull-back and reveal. But it was brilliantly done. And another great lesson.

Around this time, I managed to wangle a whole month’s holiday out of BMP.

I felt pretty pleased with myself and came back to work relaxed and rested.

Only to find that an emergency brief had come in on one of my accounts while I’d been away.

(This was back in the days when your account team didn’t call you on holiday.)

Frank had helped out, and, together with Jo Wenley, he’d created a brilliant multi-media campaign in a matter of days.

It sailed into D&AD that year, and deservedly so.

So I guess that’s something else Frank taught me: don’t take the piss with your holidays.

A few months later, thanks to a dodgy landlord, I found myself without a place to live.

I was beginning to panic when, one day, Frank said: I might be able to help.

His girlfriend had just moved in with him – so he persuaded her to lend me her flat for six weeks while I sorted myself out.

Not just any flat either.

To this day, King Edwards Mansions in Fulham is the smartest address I’ve ever been able to call my own.

So thanks, Frank. For everything.”

– TIM RILEY. (Creative)

Miller Lite.

Alliance & Leicester.

“In 1989, I joined an agency called BMP Davidson Pearce.

It was an unhappy merger between two very different cultures.

I never worked at Davidson Pearce but was paired with an ex-Davidson Pearce art director, so I was in the Davidson Pearce ghetto.

We sat on one side of the 2nd floor and “they” (Webster, Tony & Kim, Frank, Tim Riley Gatley, Nick Gill, Jo Wenley, etc, etc) sat on the other and they didn’t speak to us.

But we had to do all the shit work for all the shit Davidson Pearce clients – it was like two separate agencies.

Then in came a Guardian radio brief – one brand new ad every day for a four weeks.

No one wanted to do it. I asked Keith Sands the Head of Traffic whether I could do it, I liked radio.

But The Guardian was a very special “BMP” client and it was in Frank’s group.

Keith went and asked him and Frank said no, he wanted to keep it in his group.

So I very politely went round and introduced myself.

I gave Frank my radio reel and asked him to listen to it.

If he liked it, would he let me have the Guardian brief? He did and he did.

The campaign went well, won a few awards.

Shortly after this, BMP with DDB.

Everyone on the Davidson Pearce side was fired (absolutely brutal – about ten teams).

When I was called in to collect my P45, David Baterbee was smiling.

“Look”, he said, “I’m smiling. Please relax. Frank Budgen said you’re very good at radio and he really wants to keep you”.

Without Frank, I’d have struggled.

Of the Davidson Pearce people, only Trevor Beattie was ever heard of again.

I doubt very much whether I would have been. I owe everything to Frank’s intervention.”

– PAUL BURKE. (Creative)

Southern Comfort.

“I worked at BMP for a few years with Joanna Wenley.

We had the office next door to Frank Budgen and Bill Gallacher.

I remember reading the paper one morning on my way into work and the big story was about The Hitler Diaries. Several volumes of a handwritten memoir had turned up in Germany and were said to be have been written by Adolf himself.

The story that day was that the diaries were fake.

But Papermate was one of our clients and I knew there was a topical ad in there somewhere.

So I started wrestling with a headline.

Frank came in. “What are you doing?”

“Trying to get a topical ad out about the Hitler diaries. I haven’t quite got the line yet…”

An hour later, I had something I thought was pretty good so I went to show it to Alan Tilby, who was the creative director.

“Too late, mate,” he told me. “Frank’s just shown me a belter.”

Bastard!

Frank thought it was very funny, especially when it got in The Book.

And that’s the thing, it WAS funny. Frank was so brazen about it that it was impossible to harbour any sort of resentment.

What we were all trying to do then was be the best we could be. It was an amazing culture at the time.

You’d put up all your layouts on the wall so people could wander in and offer advice or criticism.

Paradoxically, the creative department of was supportive but fiercely competitive as well.

I wrote a campaign for Knorr stock cubes but the best headline was Frank’s, when he wandered in and jotted down on a piece of paper.

Recipe for Scotch broth. First, borrow a Knorr stock cube.

I can’t remember what we were working on but both Frank and Bill and Jo and me were working on a radio job.

I tried to write something funny.

Frank did the opposite, wrote something slow and serious – and got in The Book again.

For a year or so I had been John Webster’s copywriter when he wanted one.

It was a mixed blessing. On the one hand I got to do some famous work (though, strangely, my name fell off a couple of things…) on the other, I really didn’t know if I was any good or not.

So I left to go and find out that I was just about okay. And Frank became John’s occasional partner.

Between the two of them, they had a purple period doing some fabulous TV stuff.

But Frank also was picking up awards regularly with Bill for their own work.

He really was the complete copywriter. Telly, radio, press, even a few award-winning posters for the GLC, I think.

Four years later, I went back to BMP. The agency had just bought Davidson Pearce and so a whole load of new clients, not necessarily convinced of the BMP approach, had come on board.

I was in charge of this lost while Frank was the ECD of the old BMP clients.

Again, Frank thought some of my struggles were funny and whenever we spoke, he gave that lopsided smile.

“You’re a political little fucker, but I like you” I remember him saying.

And those last three words meant and still mean a lot because, for me, Frank is right up there with Webster as an advertising genius.

What people often forget is that Frank studied photography at Manchester Art School before John Gillard persuaded him to take a look at advertising.

He had a fantastic eye.

But he really understood his craft and by that I mean that he really delved into the technology of film.

Remember Sony “Double Life”? Plenty of other ads had used the device of a single narrative delivered by multiple presenters.

What was it about “Double Life” that was so mesmerising?

The little Northern Irish kid, frowning so ferociously…”I have conquered worlds.”

Frank told me that he had shot all the scenes at 48 frames per second. In other words twice the speed film usually goes through the camera. So the actors had to slow down their speech to twice the length.

The kid was concentrating on saying his line in four seconds rather than two.

Also, when he first started directing, it was Frank who first set up a sweep of 35mm still cameras in an arc and shot a bike going through water as a kind of moving still.

Loads of people started copying it.

So many people have left agencies to go and direct and have just tilted the camera at a funny angle or slapped on an anamorphic lens to be funky. Frank always knew what he was doing and why he was doing it.”

– PATRICK COLLISTER. (Creative)

Fisons.

“I started working with Frank following the DDB merger in 1990.

By that time, I was long past being surprised by the talent in that Creative Department.

Frank was the best writer in the department (given that JW was incomparable).

He was calmly confident, sharp, and incredibly thoughtful.

He was also very kind; my marriage collapsed over a long enough period I ended up staying

in a few places, including Putney with Frank.

But what I remember most, notwithstanding my second sentence, was feeling almost

shocked by Frank’s effortless talent for the visual and visual aesthetic.

In many ways he was simply the best Art Director I’d yet encountered.

Both the HEA/AIDS print ad and the RIMMEL/SENSIQ film are illustrations.

With the Aids ad I’m pretty sure Frank said something about a Before/After shot before I’d finished reading the brief.

Not that his writing talent wasn’t useful, a debate flared up with the client, then internally,

about whether the headline on the second page should have a question mark.

To be honest I had enough on my plate, the client insisting they wanted the girl to look like ‘the girl next door’ unlike the glamourous Jerry Hall / Donovan shot in our layout.

She had to be glamorous for the ad to work – she couldn’t be glamourous for the client to

buy the ad. It was a bind, and another story.

I was grateful that Frank at least calmly closed the question mark debate by saying

something like; ‘It isn’t a question we want answered, in that regard it’s actually a

statement.’

Phew. (The only question mark headlines I like anyway are funny).”

– PETE GATLEY. (Creative)

Fosters.

“Paul Hogan, a morose and disagreeable man, insisted that Frank was out of sight when they were turning over.

The sight of Frank’s pale impassive expression used to put him off his lines.”

– PAUL BURKE. (Creative)

New Disability.

“While Frank was still a BMP creative, he was trying to become a director.

He’d heard that I’d written a TV script about disability benefits featuring Ian Dury talking to camera. Basically a radio commercial that you could see.

He appeared at my office door and asked if he could shoot it.

I said yes, given that it was such a simple job. I said to Stuart Buckley, “Do you think he’ll be okay?

Hope he doesn’t fuck it up” Imagine that, would the man who was to become (probably already was) the greatest commercials director ever be able to manage shooting one person talking to a locked-off camera.”

– PAUL BURKE. (Creative)

CREATIVE & DIRECTOR.

Clairol.

The Smith’s Greatest Hits.

Alliance & Leicester.

Knorr.

DIRECTOR.

“The most remarkable thing about the RIMMEL/SENSIQ ad was that Frank shot it.

I say that as a matter of fact.

At the time (1992, just before Frank joined Paul Weiland Film Company) Frank’s director’s

reel included a couple of ads for John Smiths, a couple for Knorr and a number for

Alliance + Leicester featuring Stephen Fry and Hugh Laurie.

All had a dialogue narrative and a budget.

This had neither, less than £20k (likely about £5k in today’s money).

It was also the first film Frank was to shoot that he wasn’t connected as Creative Director / Writer.

Frank had 100% confidence he could shoot it and so did I.

In the absence of a compatible Director’s Reel (and a storyboard) the client bought that.

We had one day, one small studio, one model, one tank of water and one table covered

with flowers, shells, pebbles and products.

I think Frank took the whole project on to give himself the pressure (or fun) of having

to find a visual narrative and one shot that was good enough to hold the film together.

He did. Trust me, given what we had, it was alchemy.

Frank was beyond unique; a staggering world class talent with the kindest heart.

On both counts, we’re all poorer without him.”

– PETE GATLEY. Creative)

Sensiq (BMP).

Harvey’s Bristol Cream (BMP).

“TO BE FRANK….NO ONE EVER WILL BE.

Frank Budgen entered my world when l met him and John Webster to discuss directing Guardian ‘Points of View’.

With a reputation for comedy commercials l wasn’t the the obvious choice, but as Frank was to go on and demonstrate no choice he ever made was obvious.

That particular commercial had a major impact on all our careers and l will be forever indebted.

In 1992, Weiland’s was fortunate to launch Frank as a new director and over the next 6 years he produced some of the most iconic work the industry had ever seen.

His approach was never conventional and in the early days l remember receiving a panicked call after a pre-prod from a well known creative director threatening to pull the job because “Frank didn’t seem to be on the same page as everyone else”. They were soon to learn that was because Frank was always 6 pages ahead of everyone else.

I felt robbed that Frank died before he got to make a movie, but he left a massive legacy in advertising that will be nigh-on-impossible to match.”

– PAUL WEILAND. (Creative & Director)

United Biscuits (Lowe).

Network Q (Lowe).

British Telecom (Simons Palmer).

“What’s he doing now?”

That’s the phrase I remember most from working with Frank Budgen.

No matter what had been agreed in the pre-prod, when it came to the shoot Frank would surprise us all by shooting strange, unexpected mystery stuff.

Like the hours spent on a shot with the lead actor scraping wallpaper off a wall despite the fact that the scene didn’t appear in the script.

The shot of the odd bloke in a bright green alien outfit who definitely wasn’t part of the plot. No one saw him in the casting and where did that costume come from?

And things like shooting through a lump of coloured glass or deliberately exposing the film so it was irreversibly grainy – all without letting anyone know about it before the event.

I made four commercials with Frank and at least two of them had an extra day of shooting tagged on.

We didn’t pay for it, it just happened. He seemed to just keep shooting until he felt the film was finished.

His super-power was an other-worldly vagueness, he was always agreeable and then he just went ahead and did what he wanted to do. At times it was like trying to communicate with an enigma from another dimension.

So in the end the best course of action was to just let him get on with it.

Fortunately he was bloody brilliant so generally it all worked out for the best.”

– MARK DENTON. (Creative & Director)

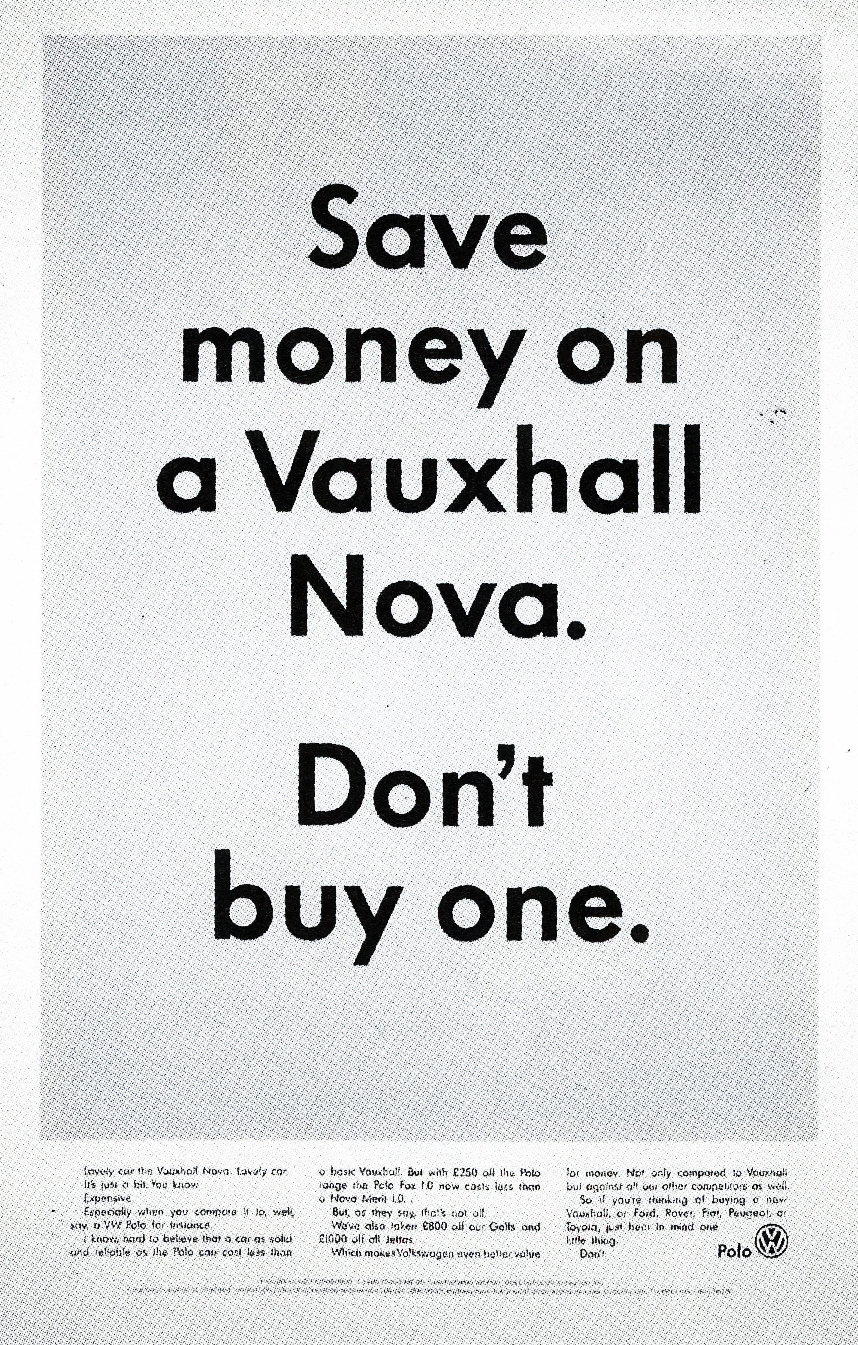

Volkswagen (BMP).

Cafe Hag.

Heinz (BMP).

Vauxhall (Lowe).

British Airways (Saatchi & Saatchi).

“Frank was part of our small advertising cabal that frequented a Soho club called Fred’s in the mid to late 80s. John Pallant, Tony Kaye and myself were the other members, Finky and Jay Pond Jones were around too.

Comme de Garcons was the “look” and the colour was any colour as long as it was black.

Fred’s had a young clientele of ambitious musicians, actors, models and other media folk and the quiet, urbane Frank, unsurprisingly fitted right in.

I remember him tall and pale and slightly awkward, nursing a half of lager that he could stretch to an hour.

He wasn’t that easy to get to know as he wasn’t the greatest conversationalist, but could become uncharacteristically animated when discussing the pros and cons of a recent piece of advertising.

Around this time Frank’s stock went through the roof as co-writer with John Webster of the Guardian “Points of View” ad, so it was a surprise to me to discover from Frank that his ambitions lay in directing.

Tony was cutting a swathe through the British commercials scene and Frank was determined to follow him.

The early 90s saw Frank’s reel developing nicely through some ads he shot for BMP. From what we could see, he was making the transition very confidently, his live action was well handled and his photography was already developing a distinctive style.

So, myself and John Pallant write a script for British Airways, Saatchis’ biggest client, an interactive idea that we know is a hum-dinger, a real “take and shake” if we’ve ever seen one!

As the brief was originally for a small poster campaign, there was no budget obvs, but Paul Arden, our ECD at the time guaranteed he’d be able to get us anyone we wanted.

We talked to many accomplished directors and purposely skirted around Frank as we didn’t want to lead him on then disappoint him, as a mate.

But, as time went on we felt we hadn’t seen the look in the directors’ eyes, no one felt as passionately as we did that we were doing something completely different.

Frank had by this time joined Paul Weiland’s Film Company, along with Paul Rothwell, so we eventually sent him the script.

From the very first response from Frank we knew we had our director, he was absolutely committed and the normally quiet, dispassionate Frank was wide eyed with a sense of purpose.

His approach to the script showed a maturity beyond his experience, he acknowledged that all he had to make sure of was that his contribution must not get in the way.

Frank “The only thing that could fuck this up is the direction!”

So, after turning down some of the most accomplished directors in London, we put our trust in the “Rooky” Frank.

Paul Arden, who had suggested a different director and an entirely unnecessary casting brief, both of which were met with stony silence from myself and John, had the right needle and was watching like a hawk,…so the pressure was on.

Fortunately, Frank came good for us, his judgement and decisions proved faultless, winning him his first major awards as a director.

Fred’s closed, Tony and Frank went on to become two of the Greatest of All Time commercials directors and Paul Arden forgave myself and John.

Over the next few years we worked with Frank on one more project as a team, though as CDs we sent him many scripts from our department only to have Mark Hanrahan, Head of TV reluctantly poke his head round our door on too many occasions with the words; “Sorry chaps, Frank has passed!”

His head disappeared before the expected riposte of “Bollocks!”

Sentimentality definitely did not cloud Frank’s judgement.

Looking back though, Frank’s judgement on those scripts

wasn’t always 100% right.

Only 98%.”

– MATT RYAN (Creative & Director)

Tesco (Lowe).

Shippams (BMP).

Danepak (HHCL).

“We worked with Frank in the summer of 1991.

It might even have been his first commercial outside of his work as a writer/director at BMP.

I can’t remember which other directors were in the frame.

They wouldn’t have been any of the usual suspects at that time as we were always keen on using up-and-coming directors.

While Frank was at BMP he had written and directed some visually funny John Smith’s commercials.

He hadn’t developed a style yet.

In fact, he ended up having multiple styles as a director but we weren’t to know that then.

We didn’t really know Frank that well. We hadn’t worked in the same agencies.

He struck us as quiet, thoughtful and diligent.

He had only just joined Paul Weiland’s production company. In an early conversation, Frank mentioned a Renault commercial titled ‘The Prendergasts’ that opened on a bird’s eye of a family getting out of the car on a day out in the country.

I do remember Steve & I were keen to start the ‘will they won’t, they reveal’ scenes as quickly as we could while the Andersen’s spoke about the benefits of Lean & Low bacon.

Frank was on for doing what was right for the idea.

The idea of using naturists and hiding their private parts came from a Hale & Pace sketch featuring an English couple (Norman Pace fully-clothed including anorak) and a Swedish couple (Gareth Hale naked in a fake blonde wig and moustache) set in a sauna.

Being Hale & Pace this was very laddish humour.

The first task was to cast actors including a baby that would credibly pass as a family of ‘naturists’.

The idea was, to all intents and purposes a testimonial so the Andersens had to be a believable family.

I think it was Frank’s idea to cast a baby which helped that believability.

It was shot in September 1991. Luckily it was an Indian summer.

No weather watching, waiting for clouds or rain to pass.

Lots of time for lots of takes especially the scene where the son has to say the crucial product line ‘And what is great about Lean & Low, this new product from DanePak, is that it is lower in fat and salt’ as he sits down in a camping chair at the same time as the mother raises the lid of a picnic hamper and strategically places a thermos flask to hide his nether regions.

Frank was keen to do a more much ambitious choreographed sequence than any in the original comedy sketch and after about 30 to 40 he succeeded.

No post-production whatsoever other than grading.

With Frank’s help, we ended up a with a commercial that felt far more Health & Efficiency than Hale & Pace but still with that visual magic to it.

Cannes Lions at that time was still a film commercials awards festival.

We had a policy of not entering awards so Paul Weiland’s must have entered the film as it won a Gold in 1992. Hopefully that helped Frank on his way.”

– AXEL CHALDICOTT. (Creative)

The Samaritans (Saatchi).

Sharwood’s (WCRS).

Kingshield (BMP).

McVities (Lowe).

Woolworths (Dorlands).

TNT.

Holsten Pils (GGT)

“Frank called me one day to say there was a particular shot in the ‘No Shit’ cinema ad we’d made for Holsten Pils the previous year that was really bugging him. It was a frame longer than he wanted.

Without really thinking about it properly I said “Frank, it’s already won a gold” – which it had.

That wasn’t the reply Frank was after.

He asked if he should speak to Di Croll who was the producer.

Di sorted it, and the version on Frank’s reel had the frame removed.

That was Frank.

Different level.”

– JAY POND JONES. (Creative)

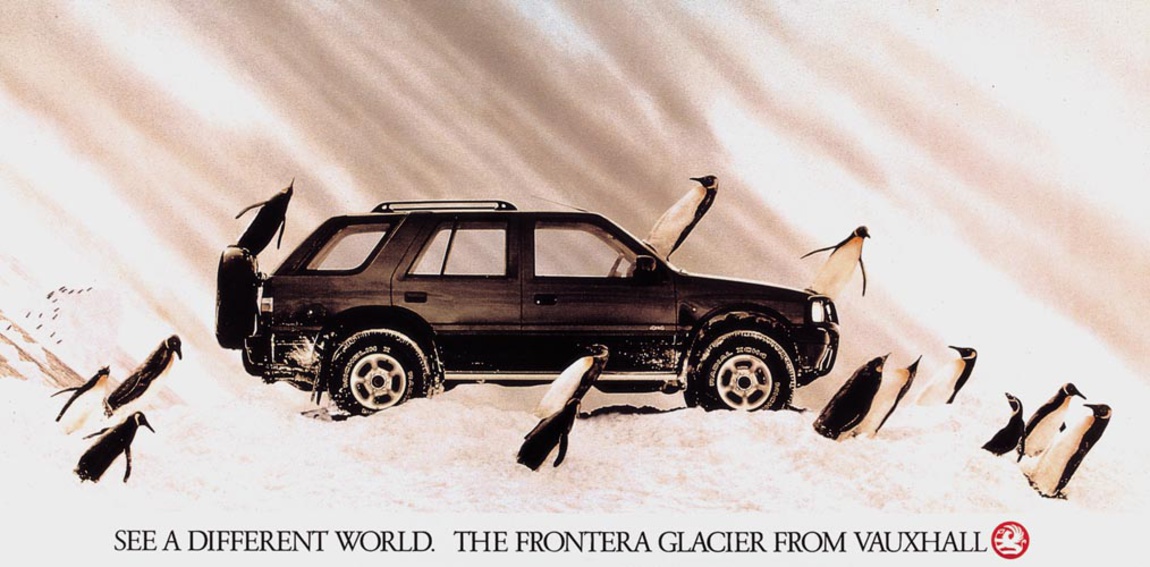

Vauxhall Frontera (Lowe).

“I worked with Frank on several occasions and it was the closest I ever came to working with a true artist.

He once said that whilst filming he had no idea what he was doing – but as long as he had more of an idea than anyone else, then that was ok.

He would feel his way into each project and it would grow organically into something unique.

Of course this drove clients mad and his non pre-production meetings were legendary.

It drove us mad too.

But I wouldn’t have missed it for anything.”

– CHARLES INGE. (Creative)

Irn-Bru (Lowe).

Orange (WCRS).

Allied Dunbar (Grey).

Pepe Jeans (Leagas Delaney).

Durex (McCann)

“Frank was a gentle, softly spoken soul, who lived in his own Universe.

Which had its own Time Zone that usually ran between 30 to 60 minutes behind GMT, but could extend to several days if an important deadline was involved.

He worked at his own considered pace and could never be hurried.

Every option was kept open the very last minute. Or later.

He didn’t so much like to leave something to the 11th hour, he enjoyed watching it cruise into the distance.

He hated reading scripts, just in case he liked one, and may actually have to make it.

According to the Laws of Aviation a bee shouldn’t be able to fly.

Similarly, Frank shouldn’t have been able to make a commercial.

He avoided meetings, decisions and deadlines.

So, on a shoot no one knew what was going on.

Neither the agency, the producers, the crew or often Frank.

Which is the way he liked it.

Despite his seemingly impractical approach he directed some of the best commercials ever made.

He elevated commercials to another level.

They still look just as good as they ever did and get better with every viewing.

He could tell a story, make things look cool, he had a great eye, style, was photographically impeccable and maybe, above all else, he had a sense of humour.

Understated, quiet, puerile and clever.

One of his perennials was calling the Jimi Hendrix album ‘Electric Landlady’.

He instantly found the funny side of everything, particularly in troubled times and dire straits.

His charm and wit, and that hint of a smile constantly hovering on his lips, meant you’d forgive him for anything.

There was only ever one Frank and they’ll never be another like him.”

– CHRIS PALMER. (Creative & Director, Frank’s Partner at Gorgeous).

Audi (BBH).

BMW (WCRS).

Kodak.

Capital Radio (GGT).

Museum Central Beheer (DDB Amsterdam).

Polaroid (BBH).

Volkwagen (BMP/DDB).

Boisvert.

Vauxhall (Lowe).

Shell (BBH).

Aramis.

Chevy.

Gossard (TBWA).

Network Southeast. (AMV).

Tesco. (LOWE)

RAC. (AMV/BBDO)

Jeep.

Volvo (AMV/BBDO).

“I feel a bit of a charlatan writing about Frank here.

I didn’t have the honour of knowing him that well.

Though, like everyone else, I loved and admired him from afar.

But I do have one brilliant short story that seems very relevant to how things are today.

So. May I?…

Braze and I had written a not particularly good Volvo script and, somehow, we’d tricked Frank into directing.

It involved going to the California salt flats and perhaps he fancied the desert air.

Anyway, he’d said yes and we were thrilled.

But this story is just about thirty seconds in the preproduction meeting.

The client (excellent by the way), the full account and production team were assembled in the big, fancy AMV boardroom.

We went through all the usual steps, guided by legendary and peerless Abbott Mead producer Yvonne Chalkley.

Everything ran smoothly, as it always did when Yvonne was around.

Then it was time for Frank to share the location pictures. He reached into his cool case… (everything about Frank was cool, if a bit weird. And the bag was no exception) …and pulled out a bunch of ten by eights.

He held them close to his chest, white side towards everyone else and quietly looked at each one.

Then he said “Yes. The location looks good”.

And promptly put them all back in his case without showing anyone.

Not the client (still excellent). Not Paul, the art director (also excellent to this day). Not me (Not bad, if you like that sort of thing).

He didn’t show anyone.

Because he’d seen them. And he thought they were fine. And he was Frank Fuckin’ Budgen, for crying out loud.

And, amazingly, nobody said anything else about them.

Can you imagine that today?

I wish you could.

Because that’s actually exactly how it should be.

You hire a genius. And just let him be a genius.

I bet God never asks him to share the location pictures.”

– PETER SOUTER. (Creative)

Olympus (Lowe).

Lee Jeans (Fallon).

Sony Playstation (TBWA).

“BEING PERFECTLY FRANK.

I miss Frank Budgen. And I’m reminded of him on an almost daily basis. Sometimes several times a day.

The source of those reminders however, tends to stir some very irrational, angry and unFrank-like emotions in me.

Lemme explain.

Frank Budgen invented The Shared Monologue. A singular piece-to-camera, divided up line-by-line between a motley crew of (very individual) individuals.

Frank deployed this technique to devastating effect for the very first time on TBWA/PlayStation’s ‘Double Life’ TV commercial.

It’s an ad which has always been close to my heart.

And an ad which began life exactly 20 years ago, when a youthful Ed Morris and James Sinclair sauntered into my office late one Sunday afternoon bearing a large scruffy piece of paper upon which was scrawled:

“FOR YEARS I’VE LIVED A DOUBLE LIFE.

IN THE DAY I DO MY JOB

I RIDE THE BUS. ROLL UP MY SLEEVES WITH THE HOI-POLLOI.

BUT AT NIGHT, I LIVE A LIFE OF EXHILARATION.

OF MISSED HEARTBEATS AND ADRENALINE…”

In capital letters.

This was what I’d call A Moment. And nothing had really prepared us for what would happen next.

But I digress. From the object of my recent daily anger: The Dodgy Double Life Doppelgängers.

Born of abject creative poverty and transparent theft and sent to invade my every waking hour, via every single charity or cause-related TV appeal.

Every bloody BBC trailer. Every gormless bastard SKYSPORTS Premier League, Open Golf or wanky tiddlywinks promo.

And now even the formerly blessed British bleedin’ Airways. All trying and all subsequently and abysmally failing to pull off the rip-off. Homage my arse.

To be perfectly Frank, they’re not fucking Frank, are they? There’s the rub, and here’s the reason.

When making Double Life, Frank shot every individual character reading the entire script, not just their specifically allotted handful of words.

This was a lengthy process, but it gave him a rich selection of performances from which to seamlessly edit and weave the transitions from one line to the next. To return unexpectedly to a character and use an extra line if their performance on the day warranted it. To switch roles. To have creative flexibility.

It’s painfully clear from the stilted edits of all the current wannnabe Double Lifers that this corner has been cut.

These pale imitators aren’t just irritating, they’ve been shot bit by tiny bit and glued together with Pritt. By prats. And try as they all might, and trying they most certainly are, none have yet matched Frank’s spine-tingling musical inspiration of bunging a classical requiem over the top. (The teenage girl vocalist with the acoustic covers hadn’t quite been born in ‘99.)

Frank tried to teach the world to shoot the shared monologue, but no one paid attention to the How. Just the Oooh.

Yet Double Life was notable for a whole variety of creative and cultural innovations.

The twirling wheelchair and dreadlocked sass of Ade Adepitan was his debut appearance on the nation’s TV screens. He’s now a national treasure.

The sheer diversity on display and startling gender voice transition through the line “Of missed heartbeats and adrenaline” seems very 2019. It blew people’s tiny bleedin’ minds in ‘99.

And yet. For all the nonsense and diminishing returns of the recent spate of doubtful Double Life Doubles, I sneakily like the idea of Frank’s stunning creative legacy being represented

by an entire genre of poorly shot, brutally edited and celebrity-stilted replicas of his wonderful original.

They are latter day Holy Relics.

They’re the faux Crucifixion Cross nails and fake Jesus foreskins for the Fortnite Generation.

What would Frank think? Frank would smile his deceptively innocent smile and ponder Take 67.

He’d ask very quietly and politely if we could squeeze another day’s shoot into the schedule. Then offer to fund it himself. Before disappearing back behind the camera.

We had some Times, me and Frank. Whether filming atop a human mountain of sweaty crazed Brazilians in Rio, debating the merits of Herman’s Hermits versus Shirley Temple (Shirley’s Gospel Train won), discovering the breathable bra benefits of Pretty Polly’s micro-fibre lining, or imagining the psychological effect of Taylor’s Coffee on the brain’s frontal lobe, Frank sought one thing. Perfection.

And quietly, persuasively and tirelessly, he found it.

More times than anyone else in the history of Adland.

We all miss Frank Budgen. And without him, the search for perfection can seem a forlorn one.

But let’s agree to book and extra day.

Fund it ourselves.

And give it another go tomorrow.

At least we can say…we’ve tried.”

– TREVOR BEATTIE. (Creative)

“We spent a lot of time chopping and changing the lines in a script.

He lived close by.

Frank.

To change the order, the logic.

I’m in post-production on my first feature and the truth is I wouldn’t have shot it if it hadn’t have been for him.

To try to find an accidental irrational intrigue or perfection.

I’ve been thinking about him lately.

You couldn’t change Frank’s speed.

So I’ve done that here in honour of him.

You and your work were profoundly authentic.

That was the exciting bit.

He never once talked about what he thought like he knew.

Thank you dearly for that.

The “what the fucks he going to do” dynamic to it all.

We’d meet in the Scarsdale tavern on Edwardes Square and chat about the work.

There’s a Bertrand Russell quote “the trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt”.

Frank liked a pub, liked a pint.

Frank was the living embodiment of intelligent doubt.

I think this played a part in his greatness too.

This seemingly pure answering only to his inner gravity gave him a very cool way.

He always had a camera on set.

Elegantly measured. Laconic. Effortlessly restrained.

Frank was also a good photographer.

I was driven partly to make a film because he didn’t.

You couldn’t quite place it.

He moved graciously, always to his own rhythm and pace. He wouldn’t be pushed or pulled.

He had this calm lower middle-English almost non accent.

I was still in my 20’s when we first shot. I knew he was way ahead of my perception.

A compliment from Frank meant something.

It’s a terrible shame he didn’t.

And the way he talked never changed in all the time I knew him.

I knew just enough thank God to shut up and listen, watch and learn.

You don’t keep all compliments, but you kept his.

One great quality to Frank was that he was a pleasure to be around.

I put that down to being very much like himself.

You got the sense that he was responding to you and the world around him in real time and very honestly.

Didn’t like sudden loud noises.

And it played out on his face.

Miles Davis said “the genius is the one who is most like himself”

There was no sense of the manufactured persona about Frank. No front, no act, no bullshit.

He had a beautiful stillness to his face.

I think a lot of the greatness of his work came from this.

He said he stayed in advertising much longer than he intended.

He seemed to have the ability to observe without the immediate leap to judgement.

Like all great creative’s he was permanently preoccupied.

He told me he hated pitching.

Painting, writing, playing his keyboard.

His powers of observation were clear, uncoloured, very real.

He eminated equilibrium.

When you were working he had this straight mid-squint, a bit like a gentle Clint Eastwood.

Zacharius, Jonze, Gondry, Frank, Glazer

And of course he seemed to always have one foot in a feature.

I’m still talking to Frank.

You got the sense that he was defending his own inner sanctum or work space with that squint.

To this day I still feel like getting him in the room, those times were three of the peaks of my career.

I’ve often imagined those conversations again and put my part right. That’s how much he means to me, that’s the depth of the impression he made.

We made three ads together.

We’d be in the edit and he would ask questions like “what do you think is more important, plot or character?”

He wasn’t going let any bullshit in.

I’d waffle my way through an answer.

I’m still trying to fashion an answer that does justice to his question 25 years later.

When you told people Frank had bit they knew you’d come up with something good.

Before shooting a frame he’d brought a scale and depth to the project I don’t think I’d ever seen before in advertising.

Back then – 90, 91, 92 – the director dream list was Spike Jonze, Michel Gondry, Glazer, Zacharias and Frank.

He came back a few days later with a track for the ad.

Tough competition to be amongst.

I remember an initial meeting we had about a script for Playstation.

Writing a script that any of these guys wanted to make was a big deal.

And that was it. Job done.

As a young creative what you made with these people changed your life. Moved you to a better agency, won awards, doubled your money.

It played a key part in all his best work.

He got a cassette tape out and played us Faure’s Requiem.

It’s one of the ways we bonded.

He’d lifted the script up to something revelatory, almost holy.

Frank had a great ear for music.

I always had a camera on his sets too.

Next time you get a moment look through his reel for music alone.

The otherness of the atmospheres, the tone or sentiment he’d find.

It’s an education in how to do it.

You realize that to do what he did you had to be somewhere very special. I think life and being alive must have been a very wonderful thing indeed with a mind like that.

He’d never flatter though, not for a moment, not how ever much work you gave him.

I would shoot film and he’d insist on seeing the negs.

My film won’t be what Frank’s film would have been.

I’m sure but it will owe much to him in many ways.

He’d keep the negs too long.

He was complimentary. He would say “you should have asked me to shoot that, and that”.

His balance of light and shade.

Through his work he showed us just a fraction of that vision and it blew us away.

Casting always.

I wish he’d shot a feature.

It was always a privilege.”

– ED MORRIS. (Creative & Director)

Free Spirit.

Budweiser (BMP/DDB).

Centrepoint (TBWA).

Inter-City (Saatchi).

Mastercard (Lowe).

Lego (BBH).

Volkswagen (BMP/DDB).

R.A.F.

Axe (BBH).

Virgin Atlantic (RKCR).

One2one (BBH).

Cancer Research (TBWA).

Nike (W+K).

Hyundai.

Guinness (AMV/BBDO).

“Frank was a beautifully odd human.

He always had an interesting take on things and was definitely wired differently than most.

A true craftsman, with great taste and a brilliant eye.

And like his famous namesake – Frank did it his way.”

– TOM CARTY. (Creative & Director.)

Pretty Polly (TBWA).

Stella Artois (Lowe).

“Frank was probably sent every script looking for a director at any given time.

So when the word came back that “he’s interested” in the one you’ve sent him it felt really special.

You had been given the chance to have an awkward meeting during which he wouldn’t say much, or seem distant, vague, or even unsure of himself.

Which would often make you wonder how he did “it”.

“It” being the creation of the finest, most eclectic, coolest reel there ever was and probably ever will be.

And trusting and believing in him meant your script had a chance of being on that reel.”

– PAUL SILBURN. (Creative)

Audi (BBH).

Southern Comfort (BMP/DDB).

Monster.

Levi’s (BBH).

Sainsbury’s (AMV).

BBC (AMV/BBDO).

“Despite all Frank’s eccentricities, one thing’s for sure, he was a very good man.

With a good heart.

Who, when he saw injustice, wasn’t afraid to step in and help out.

In an industry that by its very nature walks a fine line, honesty and integrity were important to him.”

– TIM MARSHALL. (Producer)

Reebok (Lowe).

Coca-Cola (Forsman Bodenfors).

Nike (W+K).

“So I spend many days in Toronto with Doctor Budgen shooting two Nike Spots. Tag and Shaderunning. Shaderunning required sun and we happened to be up there when it was cloudy for consecutive days.

So I got to spend a lot of time with the man and dare I say build a tiny friendship.

The one story I always recount is we’re shooting a scene in Tag and I see Frank with his 35mm camera around his neck and he would use it to frame shots.

He then had a yellow note pad with squares on it as he was constantly blocking scenes. Obsessing. Never finished and I found his interrogation of the shot, his work ethic, his scrutiny so fascinating and inspiring.

I still say, “don’t put the pen down too early” and I always think of him.

He taught me that.

I also think there was a bit of him afraid to shoot film because it was so precious.

And he knew it was a craft and that takes time.

Which is why he always had extra shoot days.

A luxury that really doesn’t happen anymore.

When we were editing back in LA I played a around of golf with Frank on a public 9 hole course.

I don’t even golf so that was hilarious.

Then I took him to In and Out Burger and I watched him eat a cheeseburger and look up at me and confirm that it was indeed delicious.

Then I took him to my favorite bar back then (now too busy) Chez Jay in Santa Monica and we drank Budweisers together.

And as I write all this I get a bit choked up because he was such a quiet yet intense soul.

He had a vision. He had perspective. And he DID NOT compromise.

And I’m certainly a better person, creative, leader because of Frank.

And goddam do I miss him.”

– MIKE BYRNE. (Creative)

NSPCC (Saatchi).

Adidas (Chiat Day/TBWA).

Playstation (TBWA).

Hewlett Packard (Goodby Silverstein).

Barnado’s (BBH).

Sony (Fallon).

Stella Artois (Lowe).

“I’ve been lucky enough to work in advertising for nearly twenty years now.

I’ve worked at world-best agencies like BBH, at Lowe and R/GA. I’ve set up my own business, Blood.

I’ve been partner in a tech investment and acquisition vehicle, You & Mr Jones. I’ve been a writer, a CD and an ECD. I’ve made print ads, telly ads, services, platforms, grown businesses, won a few awards and had a really good time in the process.

And when I look back on all that, the Mad-Men days, the Silicon Valley shizzle, the fund manager madness, if you were to ask me what the single highlight of my working career had been, since 1999, the one thing I’d take home with me, talk to my kids about, dine out on, chew the fat about with other grey-haired creative crows, then honestly, truthfully, qualitatively, I’d reply, ‘shooting a Stella ad with Frank Budgen’.

Frank was a liminal God, existing in brilliant margins just beyond the talents of the creative departments of the best agencies of the world. If you were lucky enough to get a great brief.

If you were good enough to come up with a brilliant idea.

If your machine was slick enough to get your client on board. If your brand had enough clout, enough money and enough energy, then maybe you might get a conversation with him.

This was a man who had done everything.

And he was a bit weird, which helped. I once spent some time holed up in a recording studio in Boston with John Malkovic (another story for another time). Malkovic had a dislocated oddness about him.

He spoke in truncated but strung-out sentences, pausing to grasp the right word as he went.

Frank was like that as well.

Meeting him was intimidating.

We went over to the Gorgeous offices, were met by the lovely Paul Rothwell, got a wink from Chris Palmer as we walked by his desk and were then ushered into a corner office.

Frank was sitting there, staring out of the window.

We sat down and waited for him to come back from wherever his mind had taken him and Paul prompted him, maybe putting a copy of our script down on the table.

‘This is George and Johnny, from Lowe, here to speak about the Stella Artois script’.

Frank didn’t look at us. He just started talking, stream of consciousness.

It turned out he’d been sent two Stella scripts at the same time – ‘Ice Skating Priests’ and ‘Le Sacrifice’, which was ours. Frank was obviously undecided on which to shoot and was using the conversation with us to come to a decision.

We made sure he knew how ‘open’ the concept was and how true we wanted to be to the recreation of a Surrealist film.

We showed him a scrapbook of visual references we’d put together.

We stayed silent in the pauses between his sentences.

We watched him carefully for positive signs in the room, and we hoped he’d go for it.

Of course, we talked to other directors but he was the one we wanted.

The shoot was a trip.

We went to Buenos Aires.

The pre-production meeting was a phone call with the client Phil Rumbol. Frank’s storyboard was four sketches of frames that made almost no sense – perfect for a surrealist piece of work – that would have unnerved anyone but Phil.

Frank changed hotels after a day.

We thought he was trying to put some distance between himself and us.

It turned out he wanted a hotel with a pool.

We shot on antique, hand-cranked cameras.

We lost the whole of the first morning, as Frank insisted on the DOP explaining to him exactly how the camera worked and then had to work out a series of complicated astronomy calculations, to ensure continuity.

This last consideration went out of the window when we reminded him of our Surrealist intent.

Continuity was the last thing we needed.

The shoot was long, the reason for which became abundantly clear – we ended up with a five-minute cut.

Four hours were spent filming a woman weeping blood.

I’m not sure that shot ended up in any version of the ad.

It was a pleasure to work with Frank.

We spent hours and hours in the edit.

One of the proudest moments was after a long chat on client presentation tactics and expectations.

Frank turned to us and said, ‘I really like this one. I really like this one.’

He was different gravy. An auteur amongst journeymen.

I never saw him again after we worked together.

To be fair, I wandered off into the technology gold rush.

When I found out he was ill, and then that he had passed, I felt it keenly.

He was wraith-like whilst he was alive, so I imagine him haunting the corridors of agencies and production companies, groaning at the lack of purity, the dilution of craft.

The ghost of Frank should sit on every creative’s shoulder.

He had more talent than I could ever dream of.

I’m lucky to have worked with him.

His reel was interstellar.

I don’t think we’ll see his like again.

Times have changed.

The paradigm has shifted.

What a man.”

– GEORGE PREST. (Creative)

Xbox (72 & Sunny).

Mercedes-Benz (Campbell Doyle Dye).

“One story that always springs to mind whenever I hear his name.

During the pre-production, a young producer had to leave early, they had tickets for a film premier.

Someone asked what they were seeing.

‘Stoned’ about the death of Brian Jones…in the Rolling Sto…’

‘What?’ asked Frank.

‘Stoned?’

Frank looked shocked.

The room fell silent, people imagined why this news was so disturbing.

‘I was still thinking about it…I haven’t passed on that yet?’

It was appalling, whilst Frank mulled over whether to shoot this film, the low-life production company had approved another director, got the finance, gone into pre-production, shot the film, post-production and were now only hours away from its premiere in Leicester Square.

What gits!

It stuck with me because it’s so pure, innocent almost.

No glad-handing, hoop-jumping and all the other bullshit you have to do to make a feature.

Just a total focus on the product.“

– DAVE DYE. (Creative)

Sony Playstation (Fallon).

“I never actually got to work with Frank.

I was busy on other stuff when Frank did the Play-doh thing with Juan.

We had a chat or two during that, but that was as close as I ever got.

I am a huge fan of Franks.

Both as a creative and a director.

Every time I sent him something I would take a deep breath and then pray.

He always passed.

It was a funny feeling running a pretty good agency, getting agency of the year accolades and plenty of awards and at the same time being scared to send a script to Frank.

I began to enjoy how Paul Rothwell (Franks Producer) would find a different way to break the bad news so elegantly.

Frank was my barometer as to how well I was/we were really doing.

If he said yes, then you know you had a truly great idea.

When he said no, it was always with a razor-sharp reason.

Like I said, he always said no.

But I loved that he was there to inspire from afar.

To show that there was a level above.

And to be a teacher simply by making great work.

When you run an agency you are expected to know everything. No one does.

But, for me, Frank did.

And I can’t thank him enough for being so brilliant.”

– RICHARD FLINTHAM. (Creative)

“I remember spending time with him in the edit suite.

He was making lunch orders very complicated and specific – day in and day out.

Also coffee or flat white requests, etc.

I was simply observing all this.

Everything mundane became like a life and death matter somehow. Almost an obstacle. Which I found equally funny and disturbing.

But he was making a point – I think- to everyone in the room. Everything in life could be specific if you want it to be.

And that’s how he made outstanding work.

Like deconstructing reality and building it back.

Every day he’d ask what this small Italian place made for specials… he’d have a runner or an assistant call the place and ask what appeared to be random questions.

But they weren’t random.

‘Where’s the egg from? How’s it cooked? What do you mean by ‘greens’?’ Etc, it was endless. And fascinating.

Translate all that painful desire for specific answers, to what he made the animators at Passion go through one month before we even got scouting in New York to shoot Play-doh.

At the beginning, he questioned the animators as if he was a 5 year old. Literally as if he didn’t know anything.

But he obviously did.

He just pretended not to know.

Eventually, that dynamic would change, it became like an interrogation room, he wanted to know precisely what the process was like, (probably because he had a better process or simply didn’t want to leave anything for granted).

No conversation could be rushed.

Remember, Frank was unable to order fish and chips simply. “What fish?”

“Which sea?”

“What depth?”

“Which temperature?”

I think he invented the Flat White.

I’m sure the animators have nightmares about Frank today. And absolute respect too.

It was the closest to watching the ‘I play the orchestra’ scene in the Steve Jobs film (the good one).

And he never came to a final conclusion. At all.

He was shaping a sculpture from one side and then he would walk away. Then he’d go back, but would focus on another angle.

People around him could become frustrated, demanding quick answers, as you’d expect from a director.

He knew the answers, he just wanted everyone else to reach to the conclusion with him.

I must add, he was very gentle when asking questions.

Almost in a demonic way. But I insist, super gentle.

He took control of whatever room he stepped in.

He was slowly making everyone aware that life is not just what you get, but what you make of it.

And he demonstrated his particular vision in his films.

On each shot.

On each frame.

I remember him shooting this Chinese guy on the street wearing a t-shirt that red ‘Happy Ending’ Massage Parlour. He was so happy.

It made the cut of course.

I remember going for dinner years later to an Italian place.

We were four around the table.

The waiter came and asked ‘Ready to order?’

I started smiling.

I miss him.”

– JUAN CABRAL. (Creative & Director)

“I worked with Frank on Sony ‘Play-Doh’.

I played through for the last time, to check the final mix, when the ad ended I turned around to look at Frank to check everything was ok.

He looked at me and said that’s “Great Parv, but why put the sound of a sweet wrapper in there?”

(Someone unwrapped one of our studio sweets in the middle of the playback.)

I replied “Erm…it wasn’t intentional, shall we play back and check it again?”

I did so.

No one in the room moved an inch.

“That’s perfect Parv…did you take it out?”.

“Er.. yes” I replied.

“Excellent! Sounds great.”

– PARV THIND. (Sound Engineer)

British Heart Foundation.

“Frank Budgen understood advertising.

He was an understudy to the equally brilliant John Webster at BMP.

John knew that entertainment was absolutely vital as an included ingredient in the making of a commercial.

The final little movie should not elicit intellectual comments like “Oh that’s funny!” or “Yes that is a wonderfully effective selling message.”

It should make the variant incumbent hostile audiences go “ HAHAHAHAHA!!!!!” or “WOW!”- Frank went from there.

He was focused and became a very good businessman in the sense of knowing how to restrain himself from ever getting too emotional or attached to a project at the outset.

He built and created a deep understanding with the creative team and agency producers that he was working with to elicit the most amazing schedules and budgets that almost any British commercial director ever achieved.

Hence allowing him to amass one of the finest bodies of work ever curated in the world of marketing.”

– TONY KAYE. (Director)

Honda (W+K).

Travellers.

Taylor’s Of Harrogate (BMB).

Cancer Research. (AMV/BBDO)

“Watching Paint Dry with Frank Budgen.

As those who were lucky enough to work with Frank will attest, it could be a little like watching paint dry.

Frank moved in Frank time.

Like a cigar-store Indian, deaf and unmoving, implacable in the face of pleading from all manner of account-men and TV producers to get a move on.

What one commentator once wryly dubbed the ‘They won’t stop till it’s shit brigade’, they had no place in Frank’s conception of good work.

He was going to carry on until he got it right.

As one of his editors. you learned a transcendental level of patience; you somehow floated above yourself, inured to everything but the need to get everything perfect down to the last frame.

To Frank the dead-line was merely a suggestion, polite guidance, meanwhile we watched paint dry.

Finally, on 11 November 2012 we filmed it; paint drying that is, but by then, did he but know it, Frank was dying.

But to begin at the beginning, or my own beginning with Frank at any rate.

Back in 1992, having seen my then main client, Tony Kaye, head State-side, I was looking for new directors.

A producer friend suggested I try the up and coming tyro directors Frank Budgen and Mike Stephenson at The Paul Weiland Co.

‘But!’, she warned me, ‘toss a coin, approach only one’.

It came down heads (Frank) – lucky me.

So began the best part of a decade of exhilaration, exhaustion and frustration in equal measure.

A wide variety of work followed; from the comedy of Virgin’s grim reaper to the cool artfulness of Orange’s launch ad with a floating baby, BMWs bent out of shape in the Nevada desert to men dragging live crocodiles behind them in the swamps of Florida.

His breadth was nothing if not extensive.

The experience of cutting for Tony Kaye, as a complete novice, had taught me to edit, but working for Frank was completely different; he taught me to think.

Not for Frank the improv jazz approach of Tony.

No, for Frank every last word, dot and comma of the agencies script was interrogated for meaning.

Eventually, towards the turn of the century, our paths drifted apart, me into more feature based work and Frank into even bigger things in America.

So in November 2012 I was delighted and somewhat surprised to get a call from Gorgeous asking me to cut Frank’s cancer charity ad C.R.U.K.

Like most people in Soho, I was aware that Frank had been battling leukaemia but I was heartened to see, when I met him again, how the indomitable quiet ‘Frankness’ was still very much in evidence.

And so in that remembrance week in November 2012 we started to film paint drying.

Quite literally. Frank’s conception was to try and replicate the Scientist’s view through the microscope of cell division by dropping acrylic paints from the studio roof onto giant 3 metre squared sheets of aluminium and then time lapse filming it drying – told you!

It worked a treat.

It worked a treat too for Frank, as I saw the process slowly re-energise him – a man who had only been discharged the week before from hospital.

Straight through the whole week in the studio and then a whole Saturday filming in a chilly autumnal Ravenscourt Park.

Perhaps one of my most poignant memories come from that day as, towards five o’clock in the dying light of a dying day Frank insisted on one more shot – nothing was going to stop him, not even the rotation of the earth.

Once back in the warmth of the cutting room his spirits revived further.

Special meals from Randall & Aubin, special pills from his complex array of medication and on we went.

Never quick at the best of times, Frank had by now become very slow indeed.

We would sometimes watch the same 3 shots on a loop for 5 minutes. But this was perhaps what made it so special; as with much gentleness one just fell into step beside him, guiding him one foot at a time through a winter blizzard as if in some Russian folk tale.

And in due course we made it back to the warmth of the hut.

Finally, nearly 3 years later one dead-line arrived the he couldn’t duck.

He was a one-off and we were lucky to have shared with him as much as we did.

He is sorely missed by all who knew him; his beautiful daughters, Toni, and his partner in crime and all-round equal and counterpart Chris Palmer.

I would love to have seen a Frank feature-film, but maybe his pace was too slow; the pragmatism and fleetness of foot, the need to compromise necessary on those projects was anathema to him.

But then again maybe not, Frank, as ever, was full of surprises.”

– SAM SNEADE. (Editor)