He changed British creativity, global advertising and the world of Art.

But unlike most big names in our business, Charles Saatchi has a tiny digital footprint, in terms of his advertising career.

Only half a dozen photos, only two interviews and just a handful of credits on Saatchi & Saatchi’s creative work.

Being slightly delusional, I’ve reached out many times in an attempt to get him to do a podcast – I’d love to pick his brain about those early Cramer Saatchi and Saatchi & Saatchi years.

My delusional attempt was via Twitter.

I searched for a likely account, I found one – a combination of Saatchi and C, filled with tweets about Art – Bingo!

As it was wasn’t open to direct messages I posted a comment on one the threads – introducing myself and asking him to do an interview or podcast.

He didn’t respond.

Obviously.

What an absolute clown! What was I thinking?

I might as well have shouted at him as he passed me in a speeding car, expecting his car to come to a screeching halt – ‘Did you say podcast? Me? Why of course!’.

So in the absence of the fucker agreeing to do my podcast, I thought I’d put out what I had on him, ads I know he actually wrote.

And the two interviews he gave.

The Pre-Saatchi & Saatchi days.

Plus, an article about Charlie by John Hegarty. (Oops, that sounds wrong?)

As I was doing this I was reminded that he was the first adman I knew the name of.

A lot of my generation would say the same thing, but the reason I’d heard of him wasn’t because he was a successful ad guy, it was because my Dad used to work for him, as a decorator.

He decorated Saatchi & Saatchi’s first offices in Golden Square, then their second offices in Lower Regent Street.

This place…

For some reason, I can still remember the stuff he said about this guy in advertising, weird, because I’d have been about 11 or 12.

I don’t think I was interested in advertising at that age?

‘It’s strange, whenever you go into his office he never seems to be doing anything, never in a meeting and never has anything on his desk, he’s always got time to talk.’

Because of of this, my dad used to chat to him more than he normally would.

‘He told me that if I pointed to any advert he could tell me who’d done it.’

‘He used to say ‘you’ve got to whip ‘em and burn ‘em’.

It sounded harsh then, as I type it today, it sounds even harsher, I guess it’s a 1970s version of take no prisoners?

‘He said all his important customers won’t use the big fancy entrance on the street, they’ll come in through the little back door direct to his office.’

To me, that’s more interesting now and hints at how they operated – secret meetings, not playing by other peoples rules.

‘One day, he couldn’t park his white Rolls Royce in Regent Street, so he chucked me the keys and gave it to me for the day, I drove straight to Hoxton, hoping to bump into people I knew…couldn’t find anyone.’

These quotes were the only things I knew about advertising until, like everyone else, I read ‘Ogilvy on Advertising’ about seven years later.

It may well be his fault that I got into advertising in the first place?

Not so much the whipping and burning, more the Rolls Royces, international fame, millions of pounds and that fact my Dad thought he was clever.

Anyhow, if you’re reading Charlie, rest easy – I’m giving up trying to pin you down for an interview. (Although my Dad did say you still owe him a tenner.)

COLLETT DICKENSON PEARCE.

Selfridges.

JOHN COLLINGS.

St. Giles School Of Languages.

CRAMER SAATCHI.

PRESENTING THE SECRETS OF CRAMERSAATCHI, NOT SO MUCH A TYPE OF ORIENTAL MYSTICISM, MORE A WAY OF KNOCKING COPY. (FROM CAMPAIGN NOVEMBER 22ND 1968.)

The sign on the outer door says, cryptically, Cramersaatchi.

You walk through a quiet, busy outer office of Observer-colour plushness. There are a few stairs to double doors. Through them is an enormous off-white room, empty but for a large table.

You are in the creative sanctum of Ross Cramer and Charles Saatchi.

Cramersaatchi – it is an apt collective noun – not the advertising profession’s attempt at Oriental mysticism.

But it is fast becoming a down-to-earth advertising cult. Cramer and Saatchi are the most successful freelance team in the business, the high priests of creativity.

Art director Cramer, 31, and copywriter Saatchi, 25, have done a good number of highly regarded campaigns for major London agencies.

Yet their most important work is never seen by the public.

They have become experts at presentation work. Agencies pitching for an account hire Cramersaatchi to do a presentation campaign. The account may or may not be won, but Cramer and Saatchi move on.

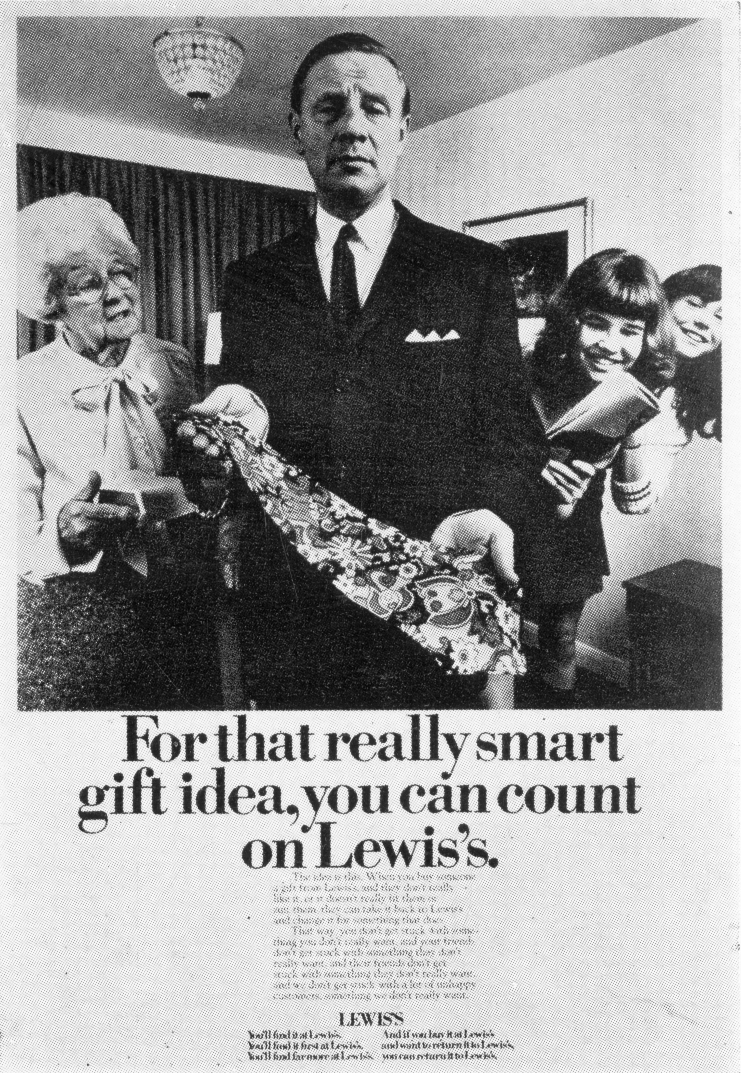

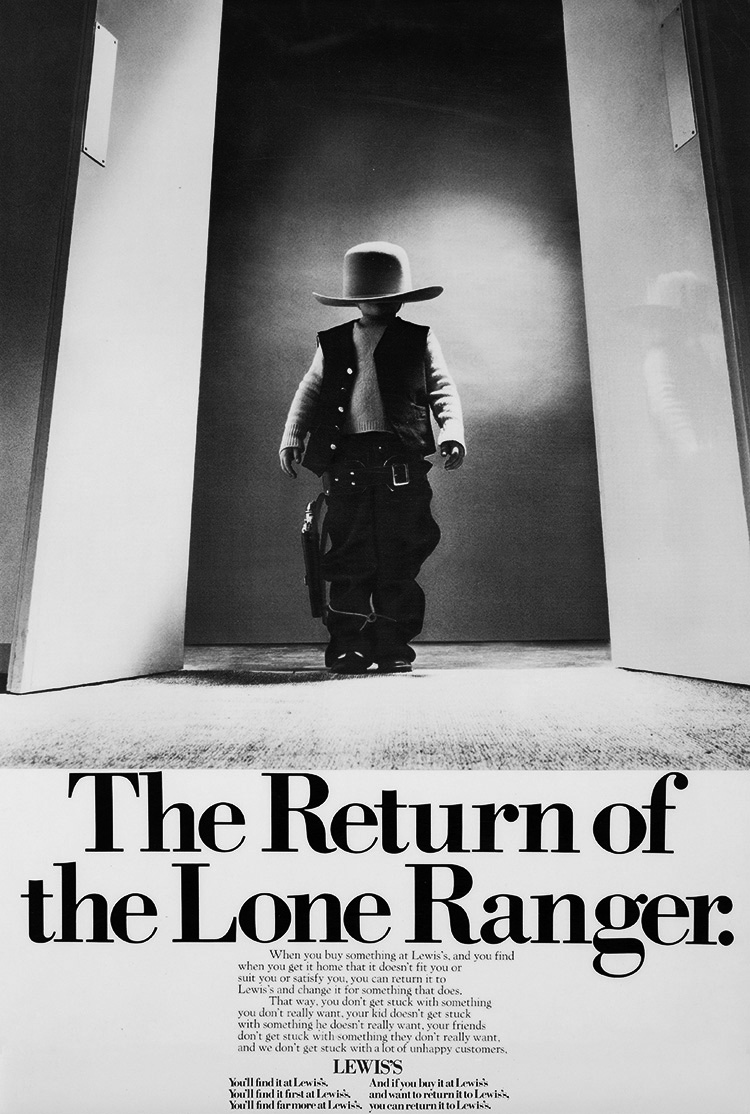

Of the campaigns that did reach the public, they created the unusual ads for Lewis stores – showing people in ill-fitting clothes, sulkily clutching un wanted presents. The copy told how you could change it at Lewis “if you bought it at Lewis”.

Everyone thought the ads were great and the client was very pleased indeed with the creative department at Collett Dickenson and Pearce.

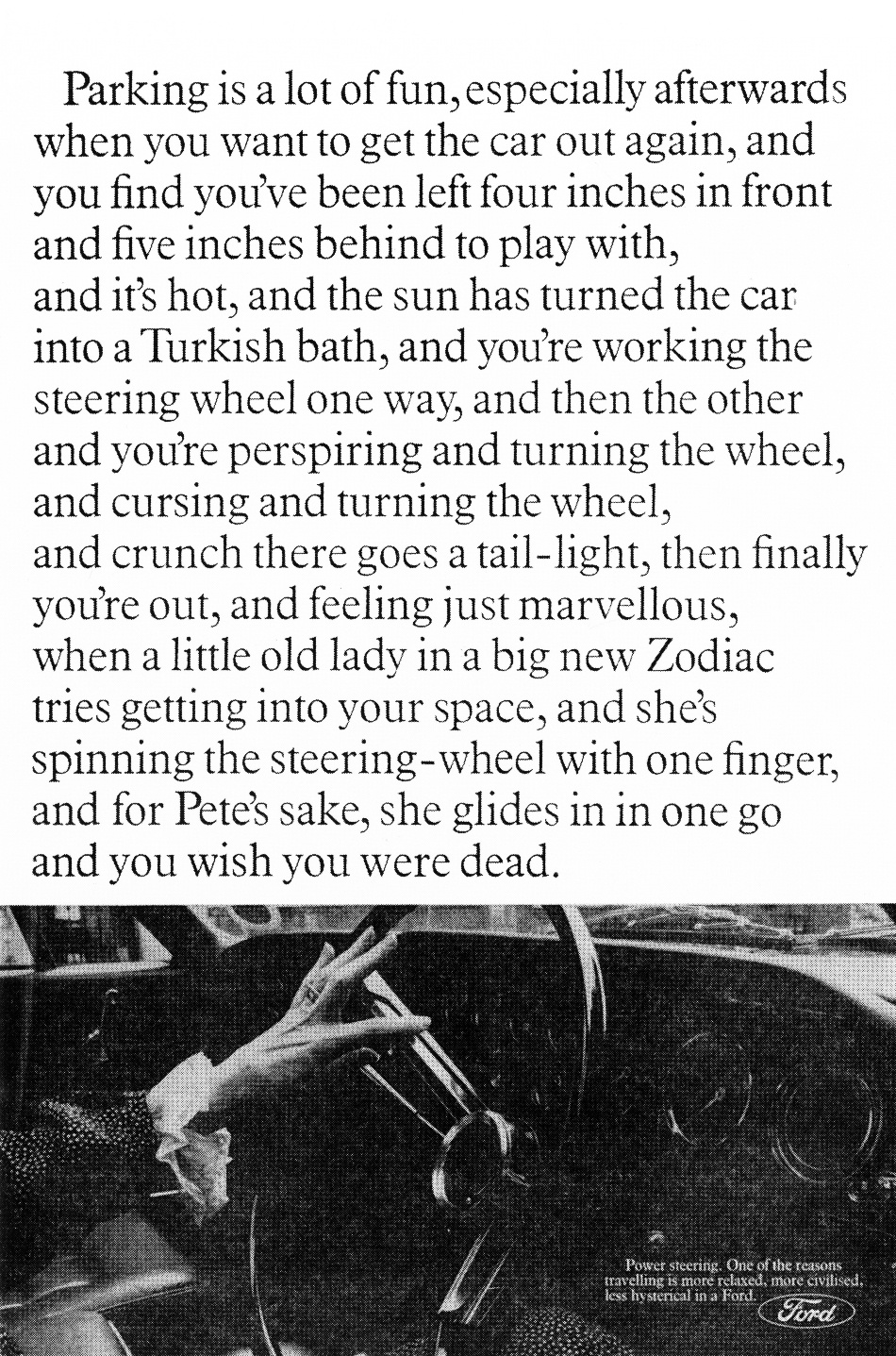

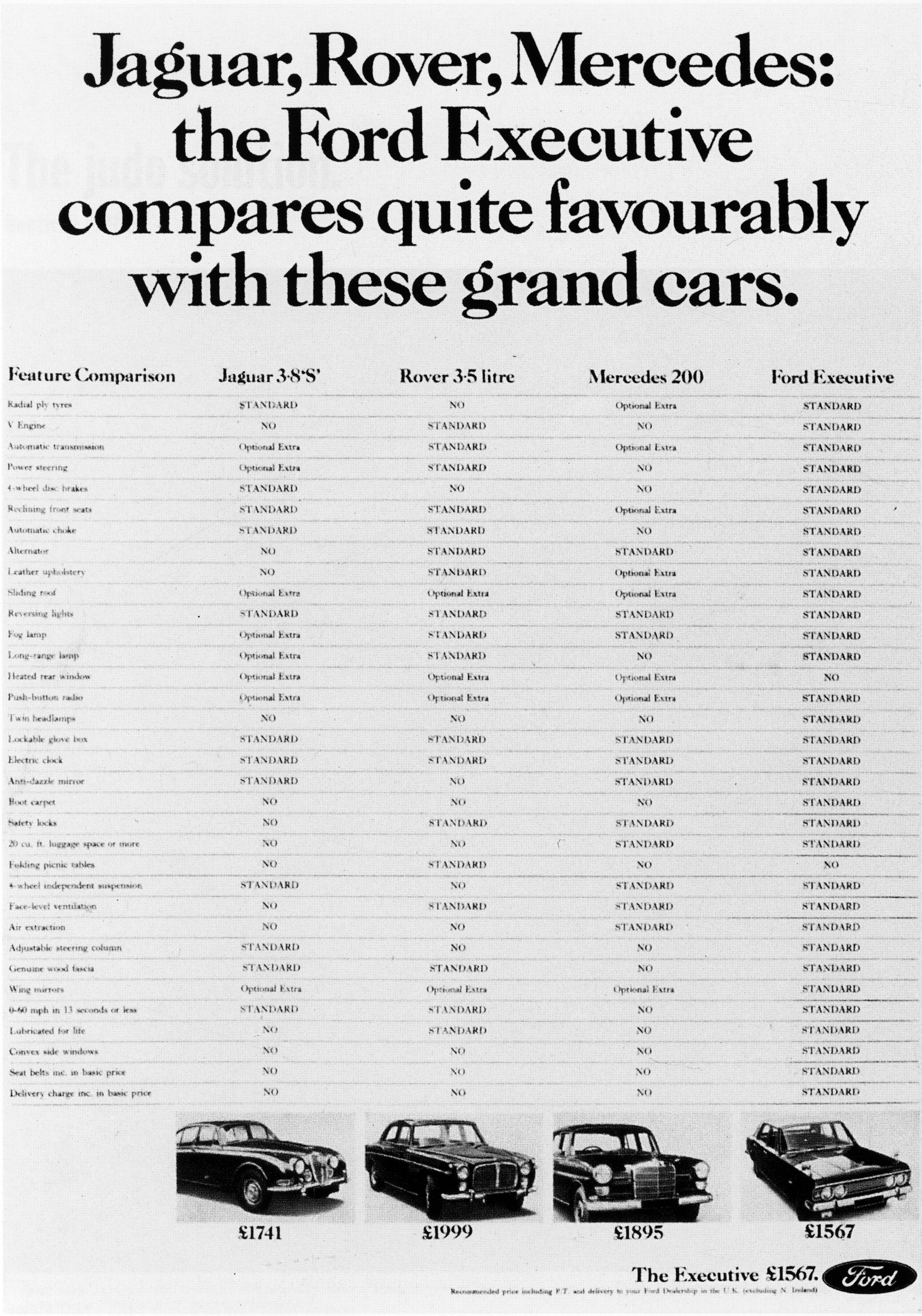

The ads which Cramer and Saatchi are most proud of and the only ones they carry in their portfolios are the famous Ford knocking ads, done when they were at CDP, and a campaign for Selfridges which was some thing of a breakthrough for store.

More recently they did the current El Al campaign (“the first Beach Bully”) and a campaign for Russian Precision watches both for the new Richard Cope agency.

Cramer and Saatchi work and talk as a pair. Cramer does most of the talking, while Saatchi merely interjects with affable indifference.

Cramer is blond, short and wisecracks continuously. Occasionally, he and the dark, broody, Saatchi click into gear when they talk and reel off unquotable phrases with gleeful precision.

Cramer defends the position of an agency which sells itself on outside talent “Some agencies feel they must not go outside the agency for creative work. But often there is a very good reason why they have to: Their creative departments just aren’t good enough. They suffer from a disease known as executive overspread.

Agencies come to us when they are up against it.

Often the creative department of the agency does something, and we do something else.

The agency chooses the campaign it likes best.

I don’t think it’s wrong for an agency to go outside. Anyway, they don’t have to get rid of us after the presentation. They can always keep us – in fact, I wish they would.”

Not surprisingly, Cramersaatchi are not too popular with a number of people who resent their moving in on an agency as if they were the ad industry’s trouble-shooters.

“It’s a bit depressing,”said one disgruntled art director,“to have these guys move in on a campaign and take the whole thing over. I’d like a few creative perks as well.”

The other view comes from the creative director of one of London’s major agencies (which has never used them) “I’d love to have those two boys on my team. They are so very good. But I could never afford to pay them enough. They are earning so much money on their own.”

The Ford knocking ads at CDP gave Cramersaatchi their name and opened doors for them. The ads compared the merits of the Ford Executive Zodiac with some higher -placed cars.

The campaign raised a lot of conservative eyebrows because it tried to do openly what all ads do secretly – say that the product was better than its rivals.

This might have been just about acceptable, but the ads actually named its competitors.

The fuss did not put them off. They unashamedly like knocking copy. Their recent campaign for the Albert film production company, a division of Associated British Pathe, offended a lot of people.

The ads inferred that agencies were being misled by many production companies who made a lot of excuses as to why their estimates were always higher and their standards lower than promised.

They also attacked the very people they were appealing to, the art directors who choose the production company.

‘And almost inevitably’, ran the copy,‘the bill from the production company turns out to be several hundred pounds more expensive than the quote – a minor detail that an extra-good lunch at the Trat can overcome’.

“We did the Albert ads direct with Pathe,” says Cramer “If we’d gone through an agency, we’d never have got them through.

Admen live in a nice closed little circle and won’t ever utter anything against their own kind”.

He defends his use of knocking ads.

“What is a knocking ad? How can you push one product without saying something bad about its competitors? If knocking ads work, then we use them.

The Albert ads were undeniably honest. They voiced what a lot of art directors feel about production companies, what Charles and I feel about them.

It’s wrong if we aren’t allowed to say these things.

If the Code of Advertising Practices had its way, we wouldn’t be able to do anything. All there would be on an ad would be a grinning face, with the caption ‘Buy Now’.”

Cramer and Saatchi met at Benton and Bowles, when Jack Stanley was creative director.

Stanley, now creative director at Dorlands, hired Saatchi “even though he had never done any work as a copywriter.

He didn’t talk a lot, but what he did say certainly made sense.

What most impressed me about him was his sense of purpose.

I teamed him with Ross Cramer, whom I had brought from Hobson and Grey, and my hunch paid off.

They made a very good team.

I think they are one of the few teams working together who will stay together for a long time.

They’re both highly critical of each other and aren’t easily satisfied.

This is a great virtue in the advertising business.

Charles is a really good copywriter. He has a lot of heart about people, which is important if you are not going to treat consumers as a lot of faceless buyers. He has great colour and a sense of salesmanship.

I knew we couldn’t really keep them. We kept upping their money, but with talent like that, some other agency is bound to come along with more.”

Cramersaatchi moved to CDP.“We did try”says Saatchi “to set up our own agency with John Collings, but it was a badly aborted attempt. Basically, I think we had no real desire to fight for minute clients.

There’s too much talk and intellectual chat in agencies. All the lovely long words like marketing strategy – they’re used to hinder advertising, not to help it.”

Having voiced the creative man’s perpetual complaint, Saatchi lapses back, with a silent gesture to Cramer to continue.

“Look at the creative scene over here. In the United States, there are over 100 top people. Over here, we know them all. Anybody who is good over here gets disappointed.

That’s why we don’t want to get any bigger.

As soon as we become an agency, we’d be bogged down with a load of useless paraphernalia.

It’s the eternal problem-as soon as you’re any good in an agency, you get caught up in the administration bog.

And anyway, we make a lot more money as we are, thank you.”

“We will cutourselves off from 50 per cent of advertisers. They’ll say we don’t offer the services. We’ll say we don’t understand what other services there are.”

(CAMPAIGN SEPTEMBER 11, 1970)

There is, you are certain, some relish in the way Charles Saatchi says, with a careful creasing of the brow: “We will cut ourselves off from 50 per cent of advertisers”.

There is self-confidence when he says that advertisers and agencies have forgotten why they spend millions of pounds a year on advertising.

There is conviction and innocence when he says that his staff will produce astonishing advertising because they are not only talented but think of themselves as salesmen of the client. And there is simply an inevitable conclusion when he says that he wants to go public in three years’ time.

In between there is either naivete or rare home-truths about the advertising industry. Probably it is a mixture of the two, but which dominates depends on your own views.

London’s newest advertising agency, Saatchi and Saatchi (his younger brother Maurice, who pleads that he is two years older than his 24) appear as natural a team as Cramer Saatchi, the creative consultancy that has now folded. But whereas Ross Cramer gave the partnership a much more relaxed atmosphere, the two Saatchis provide a double act of aggressive salesmanship.

Both are excitable, sound very much alike, use the same expressions (most advertising is either “terrific” or “shit”).

If one stops talking the other instantly takes up the script. Each is caught up in the infectious enthusiasm of the other. If they become aware that you are accusing them of over-simplification or platitudes, they are sure that you will still accept that what they are saying is true and unique to their thinking.

What they say is important and not least because of the reputation that Cramer Saatchi built up as a creative consultancy and the work that the members of the new agency have done.

But running a creative consultancy, where much of the work may be used for agency new-business presentations that can exist in marketing vacuums, calls for a different discipline from running an agency.

Many people in the industry, for instance, held the consultancy in high esteem but at the same time wondered how it would succeed in producing ads that must appear in the media.

Charles Saatchi is quick to reply: the consultancy worked for 15 of the top 20 agencies and through them for most major advertisers. He worked, he says, answering another query over his creative image, on many packaged-goods accounts and many of his ads ran in successful campaigns.

The new agency will be heavily orientated towards the creative side and Saatchi believes that the agency’s strongest selling line is the work produced by his people, particularly the two newcomers – Ron Collins from Doyle Dane Bernbach and Alan Tilby, from Collett Dickenson Pearce.

The creative stress, as far as he is concerned, means no lop-sidedness or creative-boutique tag.

Like Ronnie Kirkwood setting up his agency a year ago, he says: “We think of ourselves as a big agency. We are not interested in small clients or small billings.”

In fact, the agency says that it will not accept billings of under £100,000.

“The creative function is the main one and one of only two services an agency should provide: the other is good media buying.

They are the two services necessary to fulfill the agency’s one function – to sell the clients goods.

We don’t understand any other services.

We will not match the client’s marketing or research departments.

If we need research, we will go to top research companies outside. The point about our marketing man is that he is from the retailer’s side and so can tell the client what his own marketing department can’t.”

There are also no account executives among the working and control groups and the closer contact between the creative people and the advertiser is designed to make the creative people think of themselves as salesmen.

It will be interesting to see whether this is as meaningful in practice as the Saatchi brothers fervently believe and whether when the agency grows it will be easy to stop crystallisation of departments and the emergence of account executives.

As Maurice Saatchi himself admits: “We don’t know how the system will work.”

And his brother: “All our creative people have to act as if they were salesmen.

They have to imagine themselves in the client’s position all the time.

They have to see themselves with a warehouse full of the product which has to be sold.

Most agencies have replaced the basic function of selling with myths and mystiques about marketing and research.

But agencies and clients have become too sophisticated, whereas advertising is not a sophisticated process at all.

It is a simple business.”

They say most of the troubles of advertising stem from the advertisers’ attitude towards research.

“Companies realised it was impossible to pre-test sales effectiveness of ads but what they could pre-test was the effectiveness of communicating an idea or concept.

So communication became the criterion of advertising, and not selling.

Ask marketing directors what they want their advertising to do and too many will talk about brand awareness or creating a warm feeling for the company or improving the product image.

They won’t talk about sales.

Pre-testing on communication is only doing half the job!

Much more could be done to test the sales effectiveness of ads that have appeared – if the client really wanted to see that every penny spent was justified.”

Their attitude towards selling they say, coupled with the fact that they won’t accept accounts under £100,000, will “cut ourselves off from 50 per cent:of advertisers. Clients will say we don’t offer the services. We will say: ‘We don’t understand what other services there are’.

But whatever we say, they will never understand us.

Most advertising is ineffective. Research shows that 75 per cent of Press ads are not even read. And most of these are the work of the big, sophisticated agencies. So, they’re merely wasting the client’s money.

An agency boasts if it has increased its clients share of the market by, say, 18 per cent. Yet the odds are his ad will have been noticed by, say, 10 per cent and read by five.

That agency has done a terrible job. Had the ad been any good it would have risen much more.”

Without the motivation of selling, side events like awards become over-important. “Go into any top creative department and tell the copywriter he has put up sales of a product by X per cent, and he’ll be pleased. Tell him his ad has won an award and he’ll hit the roof with excitement.”

The setting up of the Saatchi agency comes after two years of refusals by the consultancy to accept various offers of backing to set up shop. In fact, they were offered backing when they left Collett’s in 1968 but we were not interested in a small business.

“But now we have reached the stage where we can get the clients and billings we want.

Also, it was becoming more and more difficult to work for agencies, We couldn’t agree with them or the way they operated.”

HEGARTY ON SAATCHI.

John Hegarty recalls his early days with the man whose demonic vigour launched an advertising revolution. (COMMERCIALS MAGAZINE, 1988)

I first met Charlie Saatchi in1965 at Benton & Bowles, when I was a junior art director, fresh out of the London College of Printing.

I’d been at the agency for about two weeks when Jack Stanley, the creative director, walked into my alcove and announced he’d hired a young writer to work with me called Charles Saatchi.

Jack was a lovely man who, I thought, had a lot in common with the chap at Decca who turned down the Beatles.

I was full of trepidation.

“Charles Saatchi,” I wondered: “He must be Italian which means he can’t spell and probably lives at home with his mother.”

Monday came and in breezed Charlie. I soon learned he wasn’t Italian but I was right about the other two assumptions. (In fact, he almost got fired for a spelling mistake that appeared in one of his early ads.)

I also learned that he drove a Lotus Elan, a car not to be trifled with at the time.

I, on the other hand, had the use of o Morris Minor, but only on Thursdays. This didn’t particularly impress Charlie, but we were both, of course, unaware of the car’s future cult status.

Benton & Bowles in this period couldn’t be accused of having an enviable creative reputation, but it had some outstanding people in the creative department.

People like Ross Cramer, Sid Roberson, Roy Carruthers and Tim Warriner. (Roy and Tim soon left and went to CDP where they wrote “Happiness is a cigar called Hamlet”.)

The creative department ran what it was told to run.

We considered it a coup if our original work was shown to the client, never mind bought.

It was a major creative breakthrough if you got a full point at the end of a headline.

It was in this environment that Charlie and I started working.

Jack Stanley had put us together as a creative experiment and it was one that he began to regret very soon.

We started work on cat food – not the easiest of briefs for two aspiring creative juniors, especially as we’d probably rather have strangled them than feed them.

I remember one commercial in particular that animated a cat to Elvis Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel”.

Jack, as I recall, nearly had a heart attack when he saw it.

It was after this experience that I realised you had to take control to get your work accepted. I resolved to be a creative director.

Charlie had come to the same conclusion, except that he had resolved to own his own agency.

ln fact, Charlie’s long term vision was about ten times longer than most other people’s. And so in pursuit of this ambition and a more creative environment, he teamed up with Ross Cramer and they went to CDP.

People have often said that his legendary shyness was a show, put on for effect. It wasn’t.

I always remember the time a very beautiful temp turned up in the early days at B&B, Charlie was in turmoil wondering how he could ask her out, so Ross and I told him to give her an important piece of copy to type at 5.25 and offer to drive her home for keeping her late. “Brilliant” he said.

At 5.25 he approached her with his ‘urgent’ copy.

We all observed from a distance.

The interchange seemed to be working well until Charlie’s face suddenly dropped. He returned with a somewhat peeved expression on his face. When we asked how it went he said “Brilliantly, unfortunately.”

“What’s the problem?” we asked. “The problem” he said, “is she lives in *!!?**!” Brighton.”

By now Charlie was driving an Aston Martin, (I had progressed to a VW Beetle seven days a week), and he was one of the first of a new breed or writers, along with John Salmon and David Abbott, who were getting star status and putting their point of view across on a broader spectrum.

After CDP, Ross and Charlie set up their consultancy and asked me to join them. Cramer Saatchi proved for all of us to be a great training ground.

The security of an agency and all its structures was removed.

We had greater control but also greater responsibility.

It was during this period that Charlie’s ambitions began to become evident. He had, in his partnership with Ross, taken a back seat. Ross, at that time, was the spokesman for them both and the company.

But gradually, as Ross decided he wanted to be a commercials director, Charlie emerged as the strategist and spokesman.

Club ties and sober suits replaced the more outrageous outfits. His hair was cut and the persona of a banker emerged.

He firmly believed in not being what you expected him to be.

If the image or the agency was to be creative and youthful then he

would assume the role of being sober, thoughtful and serious.

Apart, that is, from throwing the odd chair at Maurice to emphasise a point he was making.

Another of his remarkable attributes was the ability to adapt.

Apart from his wardrobe, he also realised he needed to become a supreme publicist, which meant that his natural shyness had to be overcome to pursue their objective.

He set about creating an aura around the agency that continually made news. It reached its zenith for me with the transfer fee story.

Charlie had absolutely nothing to announce on the agency one week; no gossip, no new accounts, no new campaigns.

Something had to be done.

So it was that he decided to underline the creative supremacy of

Saatchi & Saatchi and get some column inches by insuring his creative staff for £1 million and instigating a transfer fee system if any other agency pooched them.

As we all know, it worked brilliantly with all of us posing in football team style on a bench in Golden Square and Charlie getting the story into the Sunday Times Business News.

Not bad for a week when there was nothing to announce.

Charlie believed in the juxtaposition of opposites.

A creative philosophy that he applied to his business thinking.

When Bill Atherton designed the letterhead for Saatchi

& Saatchi the brief was simple: “Make us look like a bank, everyone knows we’re creative.”

Working with Charlie honed the mind.

He was one of the few genuinely creative thinkers.

If it hadn’t been done before, that was good.

What he really wanted, though, was something that hadn’t been contemplated before.

He was the motivator behind a whole style of public health advertising that shocked in a way which didn’t allow you to ignore the message. This resulted in anti-smoking advertising that related to all smokers, describing in clinical detail what happens when you inhale a cigarette, so creating a different kind of shock advertising.

It was certainly different from the usual cliches of coffins and skulls. With Charlie’s approach nobody could say ‘but that won’t happen to me’.

He believed only in the originality of the idea. Ego was never allowed to interfere. If someone had a better version or way of making it more impactful, it would be used and they would get the credit.

He didn’t care who had the idea as long as we had one.

One enduring image or Charlie from that period will be of him wandering around the office with a layout pad seeking advice on an idea he’d had.

I always admired his ability to distance his ego from one of his ideas.

He would never be satisfied until it was perfect.

He would consult and cajole until he had achieved that goal.

He became deeply embarrassed one time about an ad that got into D&AD for D&AD’s Call For Entries.

The ad, in his view, should never have been entered, but to his horror it had actually got into the book.

His pleading with the rest of us to take credit for this misdemeanour fell on deaf ears, so his eventual solution was to dream up two creatives to take credit for him.

So were born Donald Iorio and Jake Stouer, who are immortalised in the 1970 Design & Art Direction Annual as creatives at Cramer Saatchi.

Six months after the ad appeared in the book I remember Jake and Donald being chased by a particularly gullible head hunter.

At last, Charlie was proud of the offending ad.

Around Charlie there is an ego free zone.

I’ve always thought that to be one of his greatest assets and why so many people stayed loyal for so long.

He understood that you needed great lieutenants to carry out the conquests he intended and be made his people realise that he believed in them and so they could believe in themselves.

His audacity was another of his great strengths. While everyone else would be saying “No, you can’t,” Charlie would be saying “yes you can”.

This created an ambience of possibility, coupled with the feeling, partly fuelled by him, that we were all part of a wind of change blowing through our business.

This put even greater demands on our growth and our work, which was just what Charlie was looking for.

It is this same sense of vision that has helped him build a definitive contemporary art collection. Not just in terms of purchasing known works, but by bringing unknown artists to international attention.

He wasn’t just buying art but also making names.

That’s what created power and made headlines.

This sense of achievement, of certainty in yourself, was a quality he passed onto his staff.

I know it must have hurt him deeply in the current climate when Roy Warman and others had to leave the agency.

Of course, the same applied if you left him.

I remember when I resigned in 1973 to help set up TBWA, Charlie refused to talk to me for about three years.

His loyalty cut both ways.

There is of course a dark side to his ambition. Almost anything would be considered in order to achieve the ends he desired. The objective was always to win and nothing was allowed to get in the way of that.

At times I thought the. concept of truth was stretched to the limits.

But alongside that, one has to look at the achievement and stature the agency acquired. It is all the more remarkable when you consider just how young they were when starting in 1970.

Tim Bell’s classic quip about organising client meetings after 4 o’clock because that’s when Maurice got out of school wasn’t far from the truth.

The breakthrough they achieved, guided by Charlie’s vision made for a more radical, youthful industry which has benefited us all.

Whatever befalls them at the hands of the City, that can’t be taken from them.

There are those who say success comes from being in the right place at the right time. Charlie proved that with vision and willpower it didn’t matter where you were standing or what time it was.

N.b. Cramer Saatchi work approved but not written by Charlie.

Island Records.

Interesting seeing the anti-smoking campaign here—especially since I thought they were known mostly for their Silk Cut cigarettes work (strangely missing from this compilation). And where’s their “Labour isn’t working” Thatcher campaign poster?

Hey Jeremy, I’m just focusing on ads Charlie wrote, not the whole Saatchi & Saatchi catalogue.

He was rumoured to be behind the Silk Cut idea, he obviously must’ve done a lot of other stuff, but not that he’s credited on. Dx

Here’s a link to a gallery of the Silk Cut work: https://tobacco.stanford.edu/cigarettes/modern-strategies/silk-cut-modern/

Thank you, Dave. I never knew a thing about Charles, but he sounds like just the guy I would have admired and sought out back in the day. I really responded to this quote: “All our creative people have to act as if they were salesmen.They have to imagine themselves in the client’s position all the time.

They have to see themselves with a warehouse full of the product which has to be sold. Most agencies have replaced the basic function of selling with myths and mystiques about marketing and research. But agencies and clients have become too sophisticated, whereas advertising is not a sophisticated process at all. It is a simple business.” Brilliant and still rings true today.

Hey George, glad you liked it, I love that his work is trying to win the argument, not be cool or clever. Dx

Hey Dave! Another brilliant one. It’s terrific; definitely not sh** 🤣

When I worked at Rosenfeld Sirowitz, I was in Len’s office one day. He had a huge sectional sofa and said to me, “Charles Saatchi sat right here and said ‘I want to buy your agency.’ I said to him, ‘We’re bigger than you. We’ll buy you.'” The rest, I suppose is history.

Funny.

I bet there’s a lot of Len’s out there who had similar conversations George.

Jerry Della Femina is another.

Dx

(Note to self: Stop signing off messages with ‘Dx’, not necessary – you’re looking like a rank amateur!)

When M&C first started, Charles sometimes asked me what I wanted for lunch. Thinking about it now, I should have said Scott’s, not chicken salad on white bread, with pickle.

What? You used to hang with him Keith? Dx

Wouldn’t leave me alone 😉

Today I’m having a nostalgia binge. I’ve just come across 100’s of Silk Cut miniature posters in the loft and 2 hold fond memories. They are signed by Carlos and yourself, and are dedicated to my lovely son, Nicholas (Nick). I’ve also found the Tory campaign poster miniature ‘Labour/Unions’ adjoined with handcuffs. My best years in advertising were in the 6 year period at Saatchi & Saatchi. Nothing before or after came close to the great days we had there.

All my best Paul

I fondly remember your regular visits to our office, Paul, along with young Nick. You’re right, that was a good moment to be in advertising. Kx

I mourn the loss of creative briefs like Bill Atherton’s task to “Make us look like a bank, everyone knows we’re creative”. Reminds me of the ‘3-word brief’ used to sell the film Alien to 20th Century Fox – after no other prod co would take it. The pitch just said ‘Jaws, in space’. If I write a banner ad for a bank I get a thesis. Insightful piece, Dave – thanks for taking the time to write and share it. Cheers, Marc

You’re welcome Mark. Dx

I really enjoy reading these posts. Your love for the industry really shines through.

Thanks Mark. Hope you’re well. Dx

Great stuff, Dave. So many of his ads still come across as bloody good ads, even today. I wonder if his ‘salesmanship’ style is particularly suited for press though, rather than TV, out-of-home, or Social?

Maybe Simon? Although I think you either set out to sell or you don’t.

(I’d love to know what other tv he did in this period.)

Dx

Dave, next time he asks me what I want for lunch, I’ll ask him. Oh, that’s him on the phone now.

Side point, but have his agency’s ads for the Conservative party ever been fully anthologised? I bought ‘Dole Queues and Demons: British Election Posters from the Conservative Party Archive’ but there were disappointingly few of them included.

Have his agency’s Conservative Party ads ever been properly anthologised? I’d love to see a collection of them.

Brilliant piece. Thank you. May I respectfully request that the Selfridge’s cosmetic girls image is please rescanned. Other than the headline, the narrative is blurry. Many thanks.